What are consumption-based targets? And how did Sweden become the first nation to table such an idea with support from all political parties?

The story starts on a dark autumn evening in the early 2000’s, when Friends of the Earth (FoE) Sweden held a meeting over dinner at Visingsö, an island in the lake Vättern. Two members – Björn and Magnus – began discussing the Swedish Environmental Objectives in between mouthfuls and a heated debate over the environmental objectives of Sweden, and the lack of a global perspective.

Björn and Magnus arrived at an idea: since the current environmental objectives were insufficient to capture the scale and scope of the issue, they needed to change. After all, the environmental and social harm caused by high-consumption behaviours in places like Sweden that fall on poorer communities predominantly in the Global South – who have done the least to create the climate crisis – is not adequately reflected in environmental targets. This had to change.

Consumption in Sweden

One important reason for this was that only examining the territorial impacts of consumption neglects the wider impacts of consumption beyond Sweden’s borders. In a rich nation like Sweden, we all know that the clothes we wear and the electronics we use are produced elsewhere. Consumption in Sweden requires a lot of land degradation in other parts of the world, mainly the Global South, and one of the most important reasons for species being pushed towards extinction is the loss of natural habitats, such as old growth forests. Sweden’s consumption also drives emissions of carbon dioxide, as well as other pollutants, in other parts of the world, turning the problems caused by us into the responsibility of other countries that are poorer and have fewer resources to deal with the consequences. This is totally unjust.

Thanks to Björn’s and Magnus’ discussion, FoE Sweden decided to raise the issue of the environmental objectives’ blind spot over consumption. It was a way to concretize the concept of Environmental Space that was promoted strongly by Friends of the Earth Europe in the mid 1990s. In 2004, Björn Möllersten penned a report titled “Det saknade miljömålet”, in which FoE Sweden put forward a proposal for a new environmental objective that included consumption and its impacts. Even greater was the importance of the extended and updated version of the report published in 2009, which is still being widely read throughout Sweden. A core person in this work in FoE Sweden was Annaa Mattson, unfortunately not with us any longer.

In the 2000’s, I was one of the experts in the newly set up national council of the Environmental Objectives and began raising awareness about this missing aspect and putting forward ideas to help bridge this gap. In the beginning, we were considered crazy. But, after a while, the idea got more and more support and, eventually, national authorities such as the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency and Statistics Sweden began to take it seriously and started working on mapping the climate impact of Sweden’s consumption.

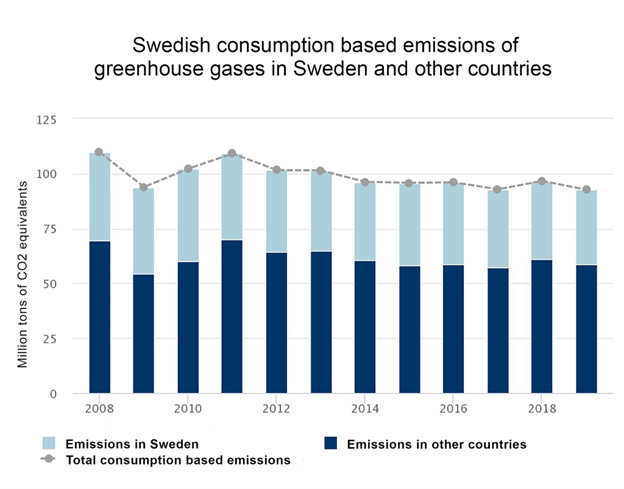

Thanks to the work completed by these agencies, we now know that the climate impact in Sweden is about 9 tons per person per year. In 2019, the total Swedish consumption based emissions were 93 million CO2 equivalents. We also know that 63 percent of these emissions are in other countries and hence not included in the territorial emissions, which are those used in international climate reporting.

Swedish consumption and politics

Partly because of the prominent work of these agencies and the advocacy work of FoE Sweden, an important decision was made by the Swedish parliament in 2010. The overall objective in the system – generationsmålet – was complemented by an international aspect: “The overall objective for environmental politics is to hand over to the next generation a society where the big environmental problems are resolved, without creating increased environmental and health problems outside the Swedish borders”. This was a huge victory – and it made it vital for the national agencies to measure and map the impact of Swedish consumption.

A few years later, the Green Party was in government and initiated the process of a national Climate Act. The Green and the Left Party tried to include a consumption-based target in the climate act, but the other political parties were not ready to take such a step and blocked it.

During the drawn-out negotiations to form a new government in 2018-2019, the Green Party succeeded in getting an agreement for a parliamentary investigation by the environmental objectives committee to investigate the issue of consumption-based targets and the feasibility of integrating them into Swedish climate policy and reporting.

The right-wing parties did not take to the idea, but after lots of struggle, delay, and negotiation, the result was a proposal from all eight political parties in Parliament to introduce a consumption-based climate target. There is still no formal decision, but since all political parties in parliament agree — it is just a matter of time. Or should be. You never know what will happen with the new government that has been instated following the recent elections on the 11th of September. The new government will consist of right wing parties, with the support or inclusion of the extreme right, which has become the second largest political party in Sweden.

The proposal is both praised and criticised. Praised because it puts forward a completely new angle on climate politics and makes it necessary for the government to find ways to decrease the climate impact of consumption. And simultaneously criticised for being too weak and “fluffy”.

Ultimately, it is a big victory that emissions from consumption are to be included in the political system and the climate goals. The big Swedish NGO’s such as WWF Sweden and The Swedish Society for Nature Conservation maintain that this is a unique proposal internationally and a very welcome one.

But there remain loopholes and the potential for failure. The introduction of a goal to increase the climate efficiency of Swedish exports, for instance, was an important victory for the right wing parties in the committee, since they believe that Sweden’s exporting efficient technology reduces emissions in other countries. This might be true in some cases, but it is rather vague and not easy to calculate. The committee also failed to set a target to diminish the emissions from air travel by Sweden’s population, which was a huge disappointment.

What conclusions can be drawn from all this? And can this approach to climate accounting become a blueprint for other nations to follow?

- A rich welfare nation is admitting that its consumption has an environmental impact in other countries, and that there should be a target and political action to diminish them – at least for the climate aspect of consumption. It makes it a lot easier for other countries to follow – which is of great importance.

- One of the key factors in FoE Sweden’s strategy was to work within the system – the national environmental objectives – to widen their scope to include ideas outside the system – environmental space. This strategy was very successful.

- It shows that environmental NGOs and civil society have a crucial role to play in putting forward new ideas and perspectives even if the victory comes many years later.