We need large scale, systemic change if we are to meet the 1.5˚c warming target set out in the IPCC Paris Agreements. In this guest post, Lisa Luna from Climate Action Tracker, talks about the decarbonisation and transformations required in the high emitting sectors of power, transport and industry to achieve this goal.

For the past two years, the Climate Action Tracker has been producing a series of memos that look at the decarbonisation required in high-emitting sectors to meet the Paris Agreement’s 1.5˚C warming limit.

The latest paper in our decarbonisation series looks at the high-speed, large-scale transformations that must be achieved on the way to the zero-carbon future required.

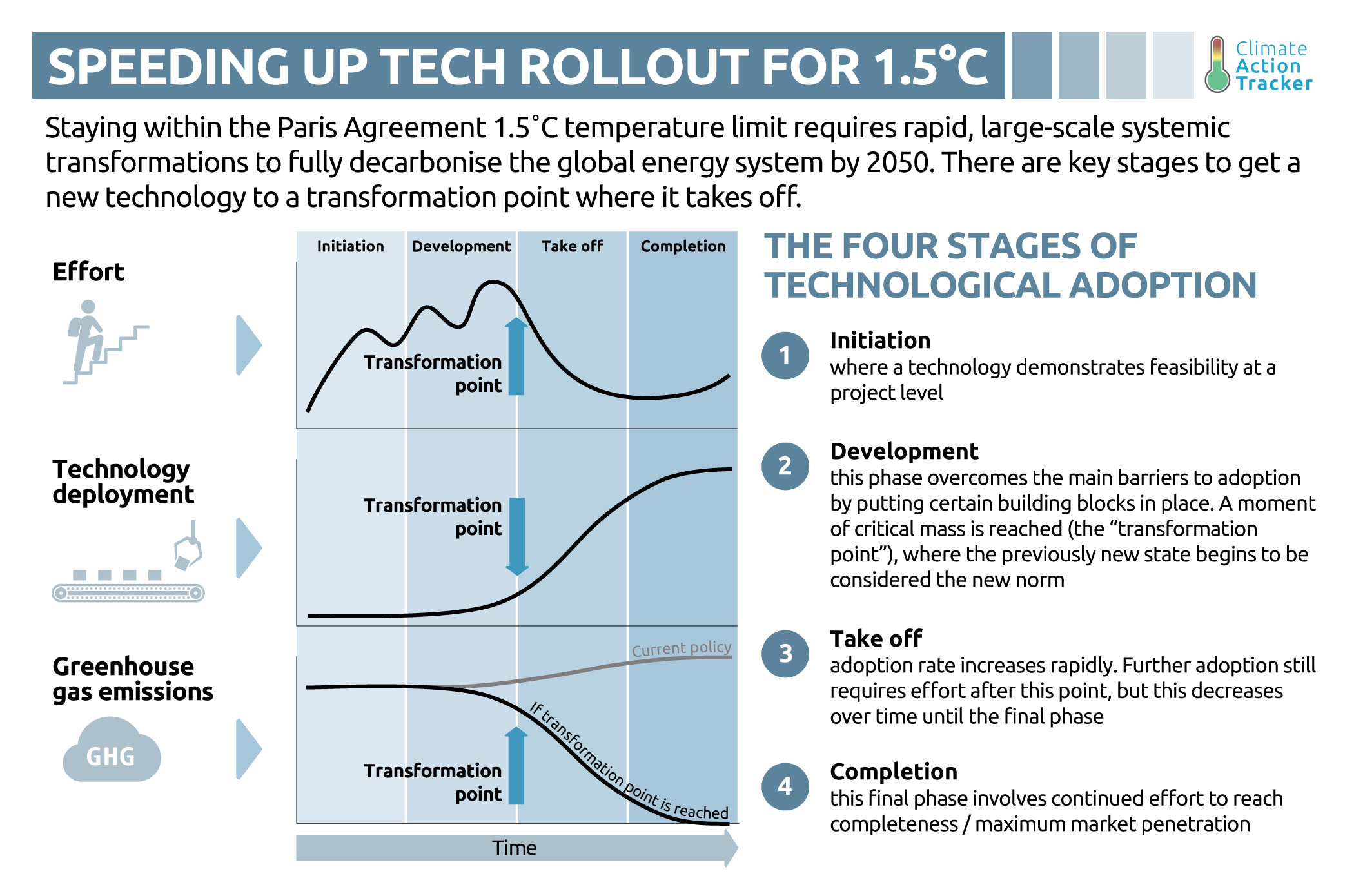

Reaching a “transformation point”—the moment when new technologies, behaviours or market models achieve critical mass and take off—can deliver the speed and scale needed.

“Transformation points: achieving the speed and scale required for full decarbonisation” discusses the general idea of what these steps toward zero carbon look like. It then examines three sectors in much more detail:

- storage for renewable energy,

- electric vehicles in passenger road transport, and

- the decarbonisation of high temperature heat in cement production.

Frontrunner governments can lead the way to the global transformation point through ambitious actions, with positive implications for all countries. The paper examines the policy action needed to overcome hurdles and kick-start the transformation for each of the three areas and looks at how far each has come in the path toward achieving the Paris Agreement goal.

For the power sector, on a global level, CO2 emissions need to be nearing zero by the 2040s. A transformation of the global power sector to 100% renewables would lead to emissions reductions of 13GtCO2/year in 2050, which is equal to China’s annual emissions today.

The first hurdles have been overcome: the levelised cost of electricity for newly-installed utility-scale onshore wind and solar PV is now competitive with fossil fuel power in many regions. Building new wind and solar is sometimes even cheaper than operating existing coal-fired power plants.

We look in depth at the next big game-changer, storage, which is close to a transformation point—but not quite there yet.

We find that, by mid-century, global storage capacity may need to be as much as 475 times higher than today’s levels, although this could be significantly lower if other flexibility measures like grid extension and demand management are deployed. Storage in the EU may need to increase to as much as 110 times its current level.

Governments can increase the likelihood of reaching a transformation point in energy storage: They can modify market rules to make storage competitive, set targets for storage capacity additions, and invest in R&D for technologies with a focus on inter-seasonal storage.

In the transport sector, change has been slower, but some regions and countries are leading the way. By 2035 most cars sold need to be zero emission. Rates of efficiency in combustion engines are growing, but are still not fast enough—and a real transformation to electric vehicles (EVs) needs to take place.

The main hurdles we identify include the higher up-front cost of EVs to consumers. An advantage is that electric vehicles are already cheaper to operate than conventional cars by a factor of two to three.

However, consumers are still concerned by “range anxiety” which is an infrastructure issue that governments need to address, along with creating more policy signals and incentives.

Decarbonisation of the transport sector goes hand in hand with decarbonisation of the power sector—electric vehicles are only as GHG emissions-free as the electricity used to power them. Even assuming that the overall vehicle fleet grows, the low-carbon electricity system, decreasing to zero-emissions by 2050, leads to a 90% decrease in emissions from passenger vehicles.

To make a transformation point in EV deployment more likely, governments can follow frontrunner examples like Norway and implement financial incentives, install charging infrastructure, and provide other benefits.

The industrial sector has made some progress, but this area needs a much more rapid rate of decrease in emissions to reach the required near-zero levels—a 65–90% reduction from 2010 levels by 2050. The next hurdle is therefore to identify and develop the combination of new and existing solutions to meet the scale and speed required.

The solutions have been technically proven at various scales, but lack large-scale deployment, underlining the need for further policy support, targeted research and development and large investments. Many zero-carbon technologies—such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) or green hydrogen are still at an early stage and cannot currently compete with established technologies in terms of production costs.

Innovative solutions such as electrification of cement making are still in the pilot phase but could reduce emissions per tonne of cement by 40% by 2030. There are promising initial developments in this sector, where some existing solutions such as low-carbon fuel switch are being deployed and could take-off more rapidly to decrease energy-related emissions.

In industry, therefore, a combination of effort is still needed, including clear policy signals and large-scale demonstration of alternatives. Low carbon innovation will need further support based on financial incentives, or financial support policies. Given the highly diverse character of the industry sector and therefore large variety of challenges in curbing industry emissions, stringent carbon pricing policies in all countries with significant industrial production could facilitate low-carbon innovation, and ease competitiveness and carbon leakage concerns. In addition, customer and public procurement preferences need to value zero-carbon industrial products.

Importantly, a constant policy push will be needed in the coming decades, as most decarbonisation solutions in the industry sector are not irreversible, making backsliding possible.

Visit the CAT’s decarbonisation page to see the other memos in the series (transport, buildings, natural gas, industry, agriculture, appliances and heavy transport).