Leeds City Council became the latest local government body to pass a resolution declaring a climate emergency on Wednesday, 27th March. It becomes part of a rapidly evolving trend recently reported on this site. Paul Chatterton, Professor of Urban Geography at the University of Leeds and a member of the Rapid Transition Alliance, has just published A Civic Plan for a Climate Emergency: Building the 1.5 degree, socially-just city – and here he writes about what that looks like in practice, drawing on his own hard-won practical experience of helping to build new ways of urban living.

We are in the middle of what is billed a ‘climate emergency’. But I’m also calling this a ‘city emergency’. Most of the world’s population will soon be urban. Cities are locked in to high energy throughputs, are responsible for about three-quarters of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and energy use, have ecological footprints larger than their city limits, and remain locked in to high-growth, high-consumption lifestyles.

In the context of growing awareness of the severity of climate breakdown, municipalities around the world are declaring ‘climate emergencies’. Tackling head-on the way we live in, manage and design cities makes sense in terms of responding to the climate emergency. Changing city life offers significant and immediate GHG reduction potential. It also offers a range of co-benefits. City redesign can address long standing urban problems – poverty, segregation, planning blight, air quality, environmental degradation, land ownership, and citizen disengagement. To embark upon city redesign in the face of the current climate emergency, civic leaders can focus on four action areas to create a roadmap that respond to the 1.5° GHG reduction challenge. Together, they represent ideas towards a Civic Plan for a Climate Emergency that can be used by policy makers, researchers, civic and business leaders alike to start to understand and take action on the scale and nature of the task.

Four areas for civic action

The first action area relates to city energy. Most cities are locked in to ageing centralised, corporate-controlled and externally dependent energy system unfit for the challenges ahead. The negative results are localised pollution, increases in greenhouse gases, fuel poverty and high utility prices.

The challenge is to embark on a large-scale shift to a city energy revolution based on an 100% municipally owned, green and affordable energy supply. Innovation needs rapidly unleashing across distributed energy networks, district heating, local smart grids, community energy, zero emissions community-led developments, Combined Heat and Power (CHP), onshore wind, solar photovoltaics, anaerobic digestion, energy storage technologies, and the new skills that will underpin these. New planning regulations and mass retrofit programmes are needed to ensure every single building becomes zero carbon. This alone is no easy task, but needs to be a policy priority with its own city directorate. Civic action will also play a role in reinforcing the need for a moratorium on fossil fuel investments and extraction.

The second area of action is mobility – the urgent task of how and why we need to unpick city life from fossil-fuel automobile dependency. The rise of the private fossil fuel automobile has brought a basket of negative consequences; road deaths, air pollution, GHG emissions, geopolitical conflict, consumer debt, status anxiety, obesity, the decline of public street life.

Action in this area goes beyond addressing the technical issues of street redesign, and the low hanging fruit of options like bike lanes, and mass rapid transit; although these are essential first steps. Given the high levels of emissions tied up in transport, to meet 1.5 targets, cities need a radically different approach to mobility – to create a socially just, zero-carbon, city-owned mobility plan. This shifts mobility away from the car by eliminating the conditions that make cars necessary. For example, by 2030, half of all journeys will need to be taken by bus, bike or walking. All remaining vehicles will be electric, or EVs. These kinds of ambitions involve comprehensively redesigning the automobile out of cities through the roll out of city-region mass transit linking all settlements with non-road mobility options, the implementation pro-walking, car free neighbourhood planning, micro-mobility options around e-Bikes, the reinstallation of integrated neighbourhood transport interchanges, the progressive closures of roads as other options come on stream, and the remunicipalisation of mobility ownership and regulation.

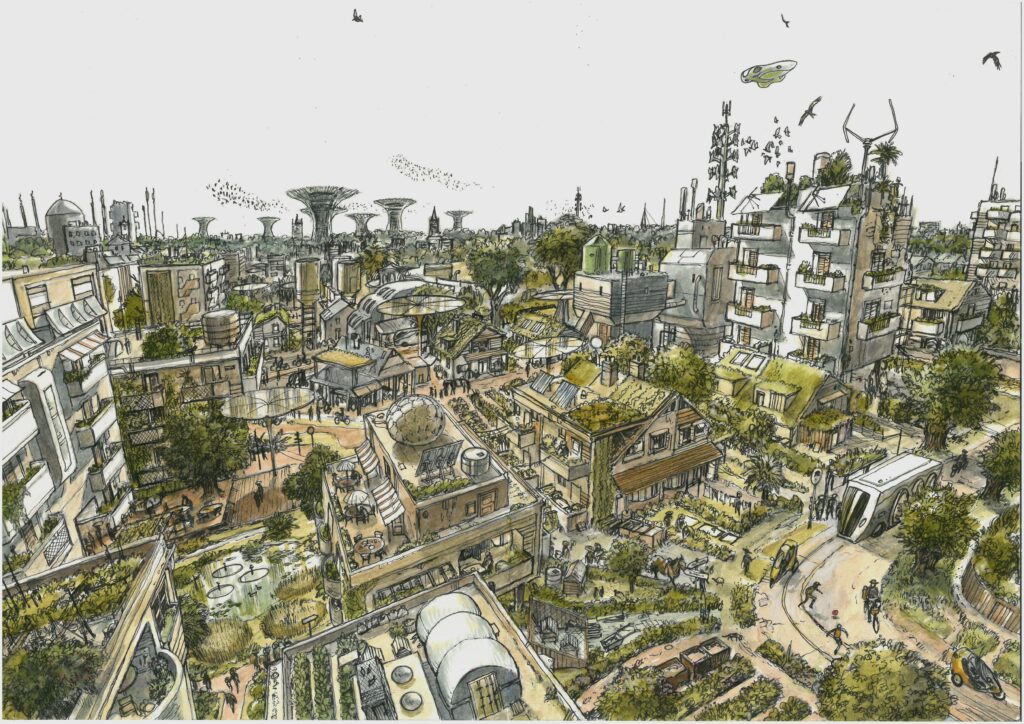

The third challenge area is to comprehensively get nature back at the heart of city development, to purify air, capture carbon, reverse species decline and offer wellbeing effects. Restorative and regenerative practices need to be central to urban policy and planning decisions. This includes approaches such as rewilding, permaculture, urban agriculture, continuous productive urban landscapes, and blue-green infrastructure. Natural systems need to be revalued not as a degradable, replaceable and free resources but playing key roles in create climate safe and resilient cities.

The final challenge area addresses the growing gap between the haves and the have nots. Civic democracy faces a perfect storm of budgetary cuts, increasingly complex problems and a legacy of silo working. All of this is eroding public confidence in the ability of municipalities to take effective action. This challenge area involves significantly shifting the function and role of the city economy so it can support community wealth building activities. Retaining and recirculating city wealth at the neighbourhood level is an effective way to create capacity amongst cross-sector civic teams so they can co-create socially just, climate safe initiatives. Civil society is bursting with potential, initiatives and skills which are effective in responding to the climate crisis and building community resilience. Examples include citizen housing, common ownership of assets, citizens forums, participatory budgets, local procurement through anchor institutions, tenant and renters unions, workers co-operatives, community-based and open-source digital manufacture, neighbourhood enterprise and maker spaces, crowd sourced city plans.

A new civic politics for a climate emergency

Declaring a climate emergency at a city level is an important initial step. But the hard work starts after this. City leaders and citizens need to carefully understand the transformative and ‘step change’ nature of the changes needed in different areas of city life as explored above. Changes will be required that will be challenging, unfamiliar and far reaching. To facilitate these, there are two important missing pieces of the jigsaw that need adding.

A first step is creating a Climate Emergency Hub. Key to unlocking rapid and meaningful change in cities is a broad and comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced and the kinds of solutions that will work. While the urgent scientific and policy messages around the climate emergency are readily available, they are inconsistently understood and applied locally. The Hub fills this gap. It initiates collaborative learning, peer-to-peer exchange, in-depth training, demonstration, information sharing and coproduction. It involves basic foundational training in key issues around the climate science of the 1.5° target as well as how these are translated into ‘step change’ city public policy choices.