Aberdeen, in Scotland, is often called the silver city due to the sparkly grey granite that many of its buildings are built with. Its other nickname is the oil capital of Europe. Since oil was first discovered in the North Sea in 1969, over 46.4 billion barrels of oil and gas (BOE) have been extracted from the United Kingdom continental shelf. Aberdeen and its surrounding areas became the hub for the oil and gas industry when it first arrived at the UK shores.

From being the oil capital, Aberdeen is now turning into an energy capital – not only for oil and gas but also for offshore technologies in renewables, carbon capture and decommissioning. The city and the wider region in the North East of Scotland have become the focus of the Scottish Government’s efforts to pursue a just transition. This blog post, based on a project of the University of Aberdeen’s Just Transition Lab, examines how just transition is understood in the city itself and what the main challenges ahead are.

Black gold in the silver city

In the mid-1960s, Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire had a static population and depressed economy, which was primarily based on traditional industries – fishing, farming, paper-making, textiles and food processing. Mechanisation and reduced demand for labour were leading to higher unemployment rates nationally and this had a particular impact in the North East of Scotland.

The first oil was brought ashore in 1975, and that is when Aberdeen’s oil boom really began with most companies prospecting and drilling in Scottish waters establishing an office in the city. This was not always easy on the local authorities and infrastructure:

“In the late 1970s between 5,000 and 6,000 people per year were arriving to Aberdeen. Over 30,000 new houses were built, 55 percent of these provided by the public sector. It still wasn’t enough; house prices and rents increased massively, house prices by over a factor of four. Schools and other services had to be built to accommodate the incoming oil men and women. Areas of the city were zoned for offices, industrial sites and warehouses; not only that, the transport infrastructure desperately needed to be upgraded”. Mike Shepherd, Oil Strike North Sea: A First-Hand History of North Sea Oil (Luath Press 2015)

After the early 1970s OPEC oil embargo, the price of crude oil was quite high and fuelled the North Sea boom until the first global oil price crash of early 1986, which severely damaged oil and gas investment in exploration and further projects, and had an impact on employment in the North East of Scotland.

Aberdeen in transition

Production was steadily increasing until the peak in 1999. Shortly after, a renewable energy focus group was formed, which later became the private-public partnership Aberdeen Renewable Energy Group; in effect the city’s first energy transition initiative. In 2001, the term ‘maximising economic recovery’ was first used, foreshadowing the main policy priority for the next two decades and counting. In 2004, the UK became a net importer of natural gas, and in 2005 – of crude oil.

Another global oil price crash hit in 2014, seriously impacting employment and housing prices in Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire. Currently, the post-covid recovery, higher oil and gas prices, as well as energy security concerns, are reigniting conversations and fast tracking licences and authorisations for petroleum production. This appears to be instilling confidence in the industry once more.

Last year, the BBC reported: “in Europe’s oil capital, everyone knows the boom times are over”.

However, despite the overall support for climate action and legislation, the climate agenda arrived in Aberdeen quite late and has sometimes been viewed as working against the regional economy. With the rise of renewables, the competition with oil or at least the perception of it was stark.

In a 2022 interview, probably the biggest figure in the UK oil and gas scene, Sir Ian Wood said:

“I spent my life in oil and gas and only about three or four years ago did I begin to get some inkling of how serious the climate emergency was…The main reason is that the North East was far too taken up with oil and gas; it was far too focused on oil and gas. Climate change is a huge issue right now, but people weren’t talking about climate change five years ago”.

It is also clear that the climate legislation will affect the labour market in Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire in the years to come. Skills Development Scotland expect a long-term growth forecast for the region to be lower than Scotland and the UK (0.8 vs 1.2 vs 1.4 respectively) over 2024-2031.

How is just transition understood in Aberdeen?

Determining what exactly ‘just transition’ means for Aberdeen requires a place-based approach to the concept. Scotland’s climate legislation defines just transition principles generally to include supporting environmentally and socially sustainable jobs, and developing and maintaining social consensus through engagement with workers, trade unions, communities, non-governmental organisations, representatives of the interests of business and industry and others.

At the local level, the Aberdeen Net Zero Route Map 2045 was adopted in 2022, incorporating ‘Fair/Just Transition’ across all working areas. The plan does not define Just Transition but mentions it alongside fuel poverty alleviation, and gender equality.

A participatory study led by the University of Aberdeen and Strathclyde aimed to understand and distil what a just transition meant to communities and civil society in the North East and to focus on building capacity for communities to engage with the process of industrial change. Traditionally the public dialogue in the North East around Net Zero and the role of the just transition has been heavily dominated by the energy industry with limited public space and debate for the alternatives. The project aimed to address this gap and provide a space for new ideas, debates and socially focused responses to Net Zero for the North East of Scotland.

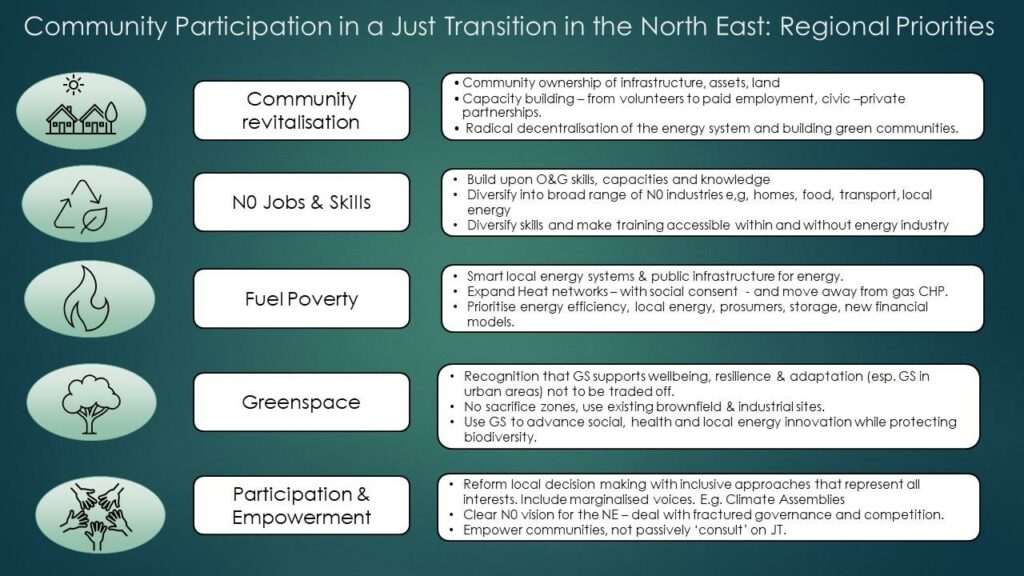

During three workshop events, researchers engaged with over 50 local community stakeholders, SMEs, local authorities and citizens in discussion about what a Just Transition looks like for the region. The identified priorities, in the image below, focused on a range of issues including Net Zero jobs and skills, but also participation and empowerment, fuel poverty, access to green spaces, and community revitalisation.

The Just Transition Lab is now building on these findings by developing a set of measurable quantitative and qualitative indicators of just transition in Aberdeen and the wider region with the goal of developing a framework allowing us to measure progress and hold decision-makers accountable.

After a knowledge exchange event with the local third-sector organisations, decision-makers, and industry leads, the researchers have narrowed down the set of indicators across four themes: 1) Jobs and skills, 2) equality and wellbeing, 3) democratic participation, and 4) community empowerment and net zero.

Challenges ahead

Building a comprehensive account of just transition from a place-based perspective, especially with quantitative measurement, presents challenges as some data is more readily available than others. For example, there is much more data around traditional employment than on green jobs and training. Democratic participation is difficult to measure and often requires a qualitative account to paint a full picture. Some data exists for recent years but has not been measured historically. Overall, we find much more information and research focusing primarily on the economy and jobs, rather than issues of equality and the social impacts of transition.

In planning for a just transition in an oil city, being prepared seems to be the main challenge. Downturns in the industry appear to take authorities by surprise every time they happen and given the inevitable decline in oil and gas production, planning ahead is imperative. Taking a place-based approach that works with and understands local culture while catering to national priorities will not be an easy task, but it is necessary if we are serious about our efforts to work towards a just transition for everyone.