The UN Climate Summit next week in New York will once again convene governments to discuss the intimidating challenge of how to coordinate action around climate change. Around the world, a series of strikes are planned to show the depth of support – led by young people, but involving those of all ages – for radical transformation. It’s a useful moment to reflect on the different strategies that we have for understanding and acting on climate change.

While climate has grabbed the headlines in a big way in 2019, it’s linked to a whole host of other challenges and changes: in development, politics, ecologies and economies.

Ensuring a fairer, more sustainable world means looking beyond carbon targets, to the social implications of different kinds of action – from local initiatives to global agreements. It matters how this is done, who’s involved, who decides, and what knowledge, viewpoints and evidence are called upon to support diverse kinds of change. So how can we provoke and guide action that might produce the transformations that are needed?

1. Strike!

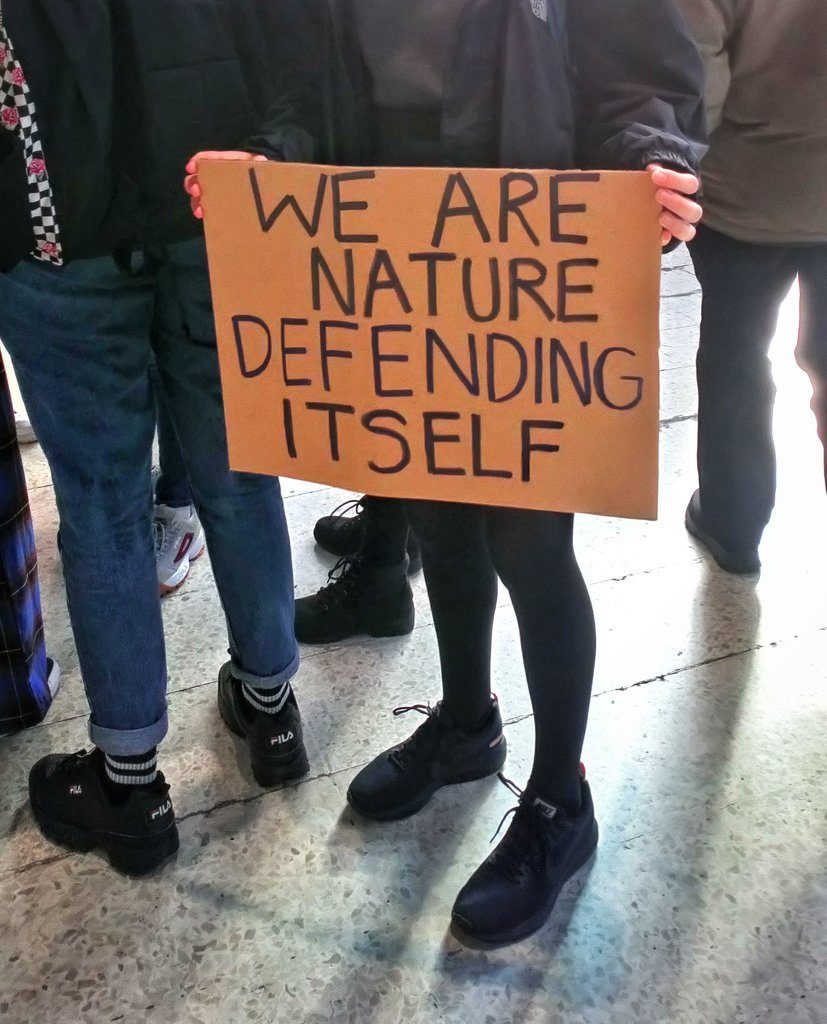

This weekend sees a global climate strike on an unprecedented scale. Millions of young people (and adults!) around the world will follow the lead of young people like Greta Thunberg, Jamie Margolin and many other visible leaders, to take to the streets and demand action on climate change.

Historical examples help to show that when people get together to fight for progress, they can provoke dramatic change. Collective action can transform those that may feel or appear powerless and allow them to challenge decision-makers and successfully affect large scale change. Evidence suggests that strikes are most effective when linked to longer-term campaigns and mobilisation for change. They can boost action from politicians who might otherwise be worried about a lack of public support for change.

2. Coordinate and negotiate

The UN Climate Summit beginning on 23 September, calls for governments to set out how they will meet targets in line with the Paris Agreement (“concrete, realistic plans to enhance their nationally determined contributions by 2020, in line with reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 45 per cent over the next decade, and to net zero emissions by 2050”). But targets are not enough, and an over-emphasis on targets can lead to perverse policies, over-reliance on technology and markets, to fix the problem. The challenge is to develop a vision of a green transformation that is led by citizens and supported by the state and other actors.

The UN agenda recognises that there are a lot of areas for action: from changing the way energy is produced and used, to finance, conservation, food systems and supporting resilience in vulnerable areas. It is not enough to have policies and plans, even if these are signed off by elected officials: the way they are implemented is also subject to politics and negotiation. The need for deliberation and involvement by citizens is recognised by many, from those promoting a Green New Deal to the climate emergency declarations of local councils and other promising initiatives.

3. Understand and share knowledge

Discussions of climate change often lead with a view of the science that focuses on modelling and observations of sea level, temperature and other biophysical effects. But many climate scientists vocally acknowledge that the drivers – and solutions – of climate problems are social too.

In the UK alone, there is a wealth of research – 481 projects since 2008, according to a recent overview – focused on understanding the social, economic and political aspects of climate change. By bringing social research and natural science into dialogue with each other, new insights can emerge – highlighting the areas where action is most needed, or economic and political barriers.

A key part of this is place-based, locally relevant research that works with people on the ground to understand how they see climate change and the other uncertainties they face. These lived experiences – from those of pastoralists keeping animals in dry and semi-arid environments, to vulnerable coastal communities, to people experiencing the mixed consequences of ‘green’ developments – can give a very different picture from the models, graphs and maps generated by experts. They can show how climate change is interlocked and entangled with various other sources of disruption and uncertainty, from industrial development to changing markets, land grabs, conflict and political or cultural change. This can help to provide more rounded, richer views of the problems people face and the responses that are needed.

4. Imagine different worlds

One of the biggest barriers to transformative change is a lack of imagination about how things could be different. The role of culture and art in provoking new visions or articulating deeply-felt emotions has been recognised by movements like Extinction Rebellion and the Culture Declares initiative – both driven by an urgent, emergency-style rhetoric around mass collective action.

But there is a long tradition of using arts and literature to create more reflective spaces to imagine how things could be different – or even show how they already are. Science fiction can be an important way to rethink people’s relationship with other creatures. Immersive experiences can be another way to create temporary spaces where relationships can be re-imagined – such as the Hidden Paths exhibition, which opens in Brighton next month, inspired by long traditions of art that engages with nature-society relations.

Creating spaces for transformation

These are only a few ways that action to address climate change can be thought about and provoked. What’s certain is that, despite high-level commitments and warm words, global efforts and agreements have failed to create the transformations that are needed, especially among the world’s most vulnerable people.

If new approaches are needed, they should include spaces to reflect more deeply on why these failures have occurred. Learning from a variety of different perspectives may help to produce new approaches together – rather than hope for powerful actors alone to come up with the solutions and responses that are needed. Allowing space for reflection and supporting more unruly and diverse mobilisations may also produce more radical and dramatic changes than expected.