This is the second blog of a series for Rapid Transition focusing on evidence-based hope from volunteer-led groups who are taking action to restore nature and tackle the climate emergency in practical ways. Thank you to Rapid Transition Alliance members and the Transition Town movement for so many inspirational stories from the UK and across their global network.

The imagination game

If someone doesn’t quite get what you mean, we often say ‘let me illustrate the point’. But what happens when you actually show them an illustration? Visual information can be processed far faster than words. We even use the word to indicate that we’ve understood something: “Oh, I see.”

Now think about drawing something that isn’t there – yet. Looking at a hillside and imagining what it might look like in a hundred years’ time. Standing outside a toilet-block and imagining what it might look like when it’s a sustainable community eco-hub. Gazing, for a long while, with what is called ‘the mind’s eye.’

What fuels the visualisation of things which we hope to see in the future is a powerful combination of observation, imagination and creation. When members of Transition Town Wellington (a group of which I am a part) had an opportunity to create a forest garden on an 8.5 acre site next to a derelict textile mill, the first thing we did was to take a close look at the ground. The lie of the land. Walking around the field, they looked at what was there: unkept, tufty grass for the most part, a dog-walking circuit, a couple of magnificent Scots pines, lots of molehills. We figured out where the sun rose and set, where the frost pockets were, where were the best views. The possibilities seemed endless – but it was hard to imagine what this place might become. We had a strong, shared sense that more trees were needed – for harvesting food from, for creating more varied habitat, for shade and for carbon capture and flood mitigation – and, not least, for their sheer beauty. A forest garden seemed like the obvious answer, but how to share that vision with the wider community, who might not know what exactly what ‘a forest garden’ that might look like?

We decided to commission local artist, Matt Slocombe, to imagine what this place might look like ten years hence. We gave him plans, and ideas, and photos. We walked around the site with him and flew drones over it. Here’s a panorama shot of the field as it was April 2021.

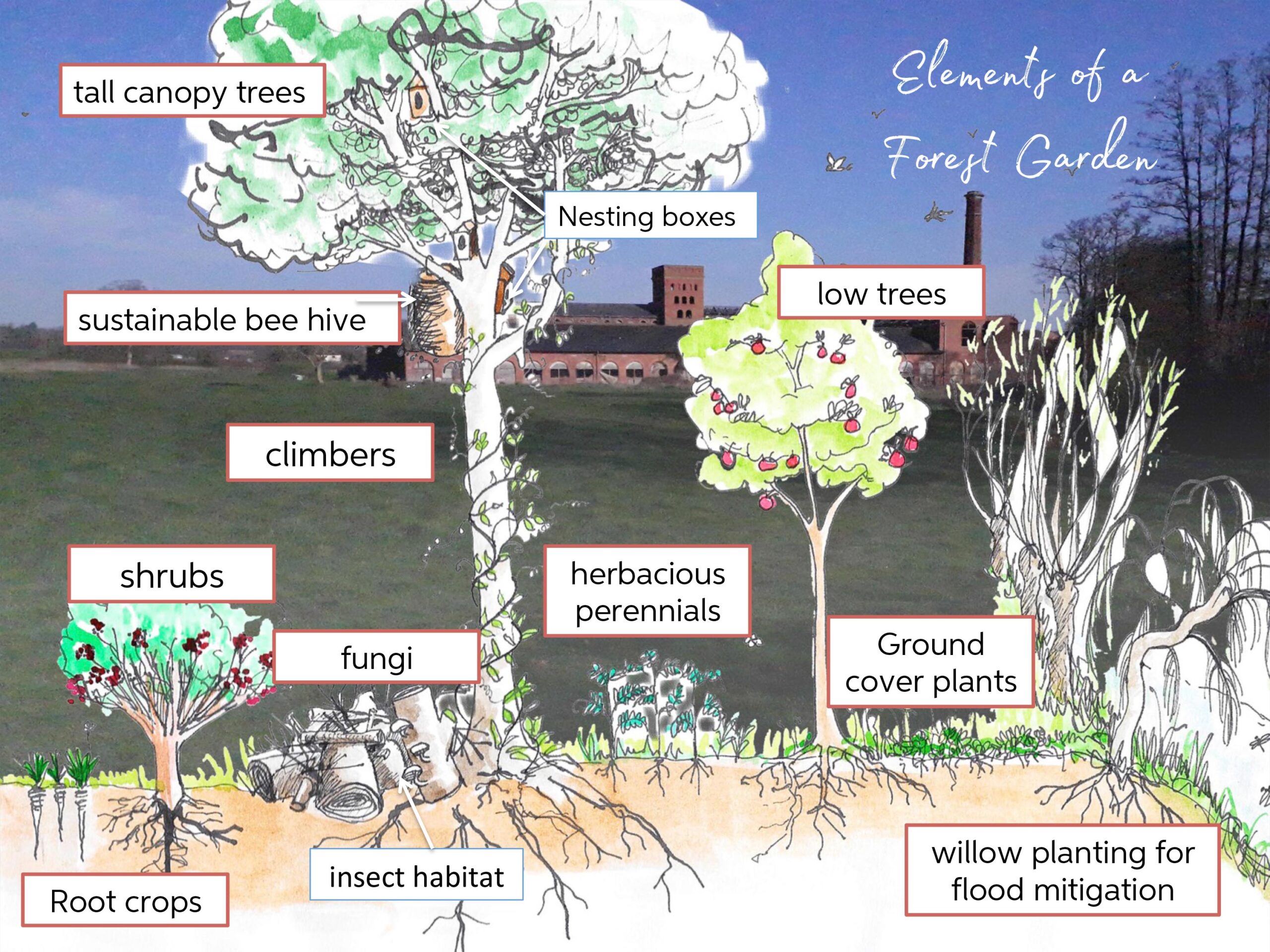

Along with photos of the site, we also gave Matt a mini-crash-course in forest garden principals, using an image I cobbled together with my rudimentary photoshop skills.

Matt took all this away, and a couple of weeks later showed us the result:

Swallows swooping through the sunlit air, a woodpecker busy on the trunk of a tree, against the beautiful backdrop of the iconic Tonedale Mill. Pathways with benches meandering under tall trees. Children playing, the wildflower meadow full of bees and butterflies. The smaller trees and bushes captured perfectly the essential feel of a forest garden: a sort of ‘woodland edge’ feel to it, with plenty of light falling to the groundcover layer, dappled shade and a diversity of micro-habitats for wildlife.

The power of illustration

We held public consultations, conducted surveys, talked to as many people as we could, created posters and displays… but nothing had quite the impact of Matt’s painting. People suddenly ‘got it’. Leaping across the ‘details-details’ that can halt an idea in its tracks, we were able to convey something of our aspirations – our wild dreams – and found that other people shared them, reflected them back, enhanced.

Rob Hopkins, co-founder and leading light for the Transition movement, is a big advocate of the visioning exercise. It goes something like this. I am a time-traveller from the future, and where I come from, all your dreams, aspirations and fondest hopes have been realised. They are done. Now what? Look around – what does this feel like, what does it look like, what can you smell and taste and feel? What are you doing?

Photography can show what’s there – but art allows the imagination to play. We can all be time travellers. Your head is a Tardis: it’s bigger on the inside.

Often, these days, the future is a scary and bleak place to be – as though the wars, destruction and environmental calamities that make up our daily news weren’t enough. But, in his recent book From What is to What if, Hopkins suggests that the key lies in telling better stories:

“We need to become willing and skilful tellers of visionary stories about How Things Turned Out OK… Many of us are resistant to these kinds of visions – they seem impossible, naïve – and yet, who can say for sure that they are any more impossible than the intellectually lazy dystopian visions we are so awash with these days?”

His book’s subtitle is ‘Unleashing the Power of Imagination to Create the Future We Want.’ What we saw with the Fox’s Field forest garden project, is that the power of illustration to create the future we want is no small thing. Fuelled by the widespread public support they saw for the forest garden, Somerset West and Taunton district council leapt at the opportunity to buy up even more land when it came up for sale in 2021. We now have the incredible situation – beyond our wildest dreams – of having more than 62 acres of green open space, protected by a 150-year lease to Wellington’s Town Council, to create a Green Corridor stretching around one whole side of the town.

This gives us the opportunity – the mandate – to manage the land for wildlife, and for people, in a way that is a brilliant example of joined-up thinking. Wellington Community Food is poised to create a community farm on part of the land, which aims to provide local people with locally grown fresh produce, year-round, using all the principles of agro-ecology. Would there be enough support for this idea?

I asked Adam Lockyear, the brains behind the community farm and head of advisory services at FWAG, what an illustration could do that all his meticulous plans and charts couldn’t.

“You can tell facts and figures to people til the cows come home, but with an illustration – it sparks the imagination. When you draw things out on a map, it looks very definite – lots of straight lines – but it doesn’t have the power of an illustration to engage people.”

Inspired by the example of Matt’s forest garden illustration, he commissioned another. This time to show people how a new community farm might look on the site ear-marked for his project.

“We spent quite a lot of time talking to Matt about the colours – so you’ve got green manure there, cabbages, purples and pinks. The poly tunnels are not to scale, obviously, but you can see how they might look.”

Lined with hedgerows, dotted with trees, these small strips of crops are a world away from what most people would picture when they think “farm”. I’m imagining, wildly, what the rolling hills of monoculture that surround our little town would look like if all the land was farmed like this…

A final word in your ear. The birds dotted around Matt’s paintings are not just decorative. “You can tell the health of an ecosystem by the birdsong. If there are plenty of birds, that means plenty of insects – and they are the bedrock for everything,” explained Andreas Hofmeyer, one of TTW’s gardening team, as we walked through the Green Corridor land this spring, our ears alert for twitter and chirrup. With our eyes and ears – indeed, all our senses – alert, and imagining what this landscape could not only look like, feel like, sound like, it seemed that nature recovery was not impossible but, with a little help from us ordinary humans, just waiting to happen.