Human beings depend on stories. We create meaning by narrativising information and sharing it with others in the form of written texts, visual art, or oral communication. Research may be fundamental to identifying trends, but it is narrative that places facts and figures in context and, ultimately, makes them useful to people.

The way that storytelling helps us engage with the world, both logically and emotionally, makes it a powerful tool. Stories invite us to imagine possible futures and remind us that we can play a role in their realisation. We might be inspired by a fictional utopia in which energy and food is freely accessible, or be revulsed by a dystopia that relies on surveillance and disinformation to control people.

How do stories work?

Although every story is different, they are governed by similar principles. Research from the Computational Story Lab at the University of Vermont used sentiment analysis and data mining to identify six basic story arcs in works of fiction.

- Rags to riches – a rise from bad to good fortune

- Riches to rags – a fall from good to bad fortune

- Icarus – a rise then a fall

- Oedipus – a fall, a rise, then a fall again

- Cinderella – a rise, a fall, then a rise again

- Man in a hole – a fall then a rise

All of these story arcs have something in common – change. Change is a driver of every story: chains of cause and effect see characters develop, for better or worse, and they in turn alter the world around them.

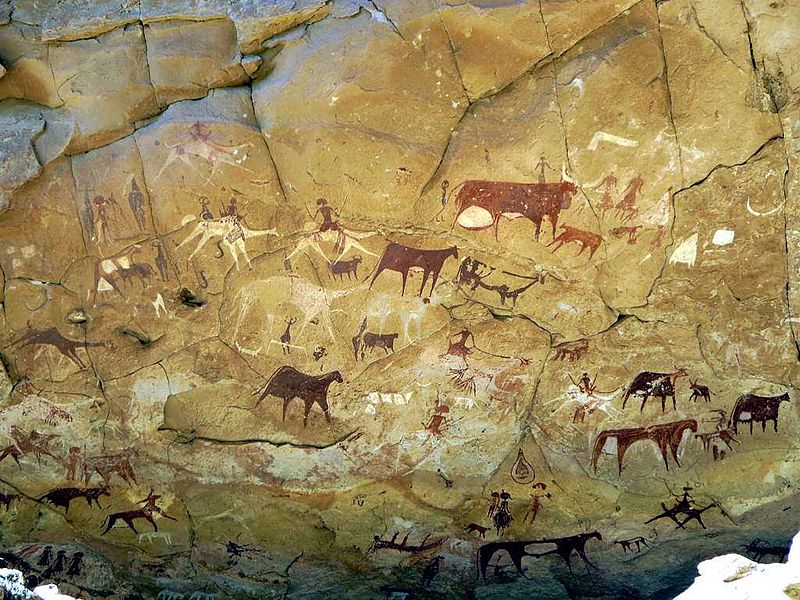

Change could be the basis of a cautionary tale – “don’t fly too close to the sun” – or an optimistic rallying cry -“things will get better”. For tens of thousands of years, we have channelled lived experience into these kinds of stories, which have been passed down through generations.

Rapid transition

We often think of change as linear. Over time, we age, species evolve, and tectonic plates shift. But change is often more radical: microorganisms, populations, and pandemics can grow exponentially.

The same can be said of our rapidly warming climate, which is predicted to lead to a domino effect of melting ice sheets and biodiversity loss. The latest World Meteorological Organization (WMO) data shows there is a 48% chance of the planet exceeding 1.5° of warming by 2026, and the IPCC predicts this will cause “unavoidable increases in multiple climate hazards and present multiple risks to ecosystems and humans”.