A decade of economic hardship seemed to have transformed for increasingly urban workforces the promise of shorter working weeks and better work – life balances into bleaker futures, of stressed commuting, working longer hours, later into life and in more precarious employment. Then lockdown struck and with it, for many but not all, slower lives, working from home and with pay underpinned by governments. But what lessons are there from working through the pandemic? Is the future of work now even harder with greater insecurity and fewer jobs, or is a new, more sustainable contract with working life now possible, along with a new understanding of what governments can do with economies?

The pandemic crisis not only has an immediate and visible impact on jobs, income, care, volunteering and leisure time, it has also created the space for ideas old and new to come to prominence, and challenge the story we tell ourselves about what is possible, desirable and feasible.

In the fourth Crisis Conversation convened by the Rapid Transition Alliance, with Compass and the Green New Deal Group, we explored issues of time, work and income, exploring how the pandemic creates an opportunity to reshape our relationship with work – paid as well as unpaid. An important angle for the discussion was how this can also strengthen our response to the climate and ecology emergency.

In previous dialogues we looked at a wide range of experiences and lessons from the crisis. Our last conversation looked at the possibilities for reshaping local, physical environments to make them more human friendly, creating more space for people and more convivial communities.

In this conversation we explored the possibilities for reshaping working lives to make them more secure, rewarding and ensure that socially useful work is properly paid and recognised.

Examples include the instant normalisation of remote working and meeting online in many sectors, former health and care workers taking up their old professions, parents home-schooling children, hospitality and other employees retraining to take up key roles in sectors with shortages. Basic income schemes are being proposed or rolled out in many places, from Spain, to the US, and the UK, while essential services being carried out by local mutual-aid groups, and there are a wealth of new online initiatives to train, engage and entertain people. Around the world, the lockdowns have also rekindled people’s interest in lo-fi activities including crafts, gardening, cooking, and nature.

The rise of the guaranteed income

Calls for guaranteed basic incomes as part of economic life have received renewed support in a range of countries since the onset of the crisis.

Patrick Brione of The Involvement and Participation Association (IPA) pointed the wide range of schemes internationally available designed to support incomes. From the UK ‘furlough’ type system, which subsidises those who cannot work because their jobs have gone into suspended animation, which he believes is, in itself, too inflexible to be the basis of long-term basic income, to the more flexible German system of Kurzarbeit. This allows companies to draw on state funding to pay people when they are working part time as well, not just full time, and could be more useful during a crisis and exist more long-term.

Leeds University based academic, Milena Buchs makes a cautionary point that what governments sometimes refer to as basic income schemes are often something else, such as one-off payments, or extensions of minimum wage schemes.

Hong Kong for example, has given a one-off paymentHK$10,000 (£985), and Japan made a one-off ¥100,000 (£930) to every citizen in response to the COVID-19 crisis. Togo is introducing a new unconditional, mobile phone based cash transfer scheme for workers in the informal sector (about 85% of the workforce) at around 30 percent of the minimum wage.

Spain announced the introduction of a ‘guaranteed minimum income’ which will be a means-tested program to fight extreme poverty, similar to the ‘emergency basic income’ adopted in Brazil.

Many governments expanded or introduced job retention schemes, protecting workers’ incomes and jobs, with the OECD country tracker keeping a comprehensive list. The UK introduced a temporary ‘furlough’ scheme, allowing employers with mothballed businesses to retain staff on 80 percent of their pay up to a maximum of £2,500 per month. Under this scheme the government is paying the salaries of around 8.4 million workers.

Several countries, including Germany, for example, have allowed furloughed workers or students in receipt of grants to take up jobs essential for the COVID-19 recovery. Many vulnerable workers however remain ineligible for such schemes.

However, experimentation with schemes in response to crises can reveal the potential benefits of novel measures and also allow rapid learning to enhance their operation. Also, familiarising policy makers and recipients with novel opens up space for long-term experimentation. Where the objective is to guarantee basic livelihood security a range of approaches are available which are not necessarily exclusive, from basic incomes, to minimum income guarantees, and the provision of universal basic services.

Rethinking what is ‘normal’ work and how it is rewarded

In the context of the UK Northern Cities Build Back Better initiative, Andy Burnham, the Mayor of Greater Manchester, said, “The traditional 9-5 working day does not work well. This is an opportunity to rethink the working day.” Kate Lister, President of the research, consultancy firm Global Workplace Analytics, estimates that, “25-30% of the workforce will be working-from-home multiple days a week by the end of 2021.”

Several dynamics about work are being reconsidered during the crisis. These range from the amount of time spent in formal work, to where that work happens, and how it is valued. Homeworking, for example, is not possible for all types of work. Care workers mostly need to be where the people are who they are caring for. Technology is still a barrier for some. And, remote working suits some better than others. Patrick Brione drew attention to the literature on wellbeing and home working and work done by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD), commenting that, for example, ‘Natural integrators find it easier than natural ‘segmenters’, and that there are clear socio-psychological benefits to having real contact with colleagues.

Jon Bloomfield, Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Birmingham made the point that physically bringing workers together can also empower them and that work is a deeply social activity, with Patrick Brione agreeing that a fragmented work force is problematic from a labour organisation point of view. Increased homeworking therefore represents a challenge for unions in how they represent isolated individual workers.

Several people, including Ruth Potts of the Green New Deal Group, and Frances Foley, deputy director of Compass, raised questions about the nature of formal work, and volunteering, the latter having risen during the crisis. Frances Foley gave the example of the balance between volunteers and paid staff being equally able to perform useful, needed work, but it being unfair to demand things equally of them. It was time, she said, to think about decoupling income and work, with the added challenge of seeing the value of greater volunteering, but the need for people to be financially secure.

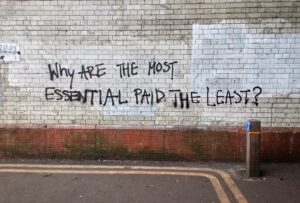

Nicky Saunter, an entrepreneur who works with the Rapid Transition Alliance, pointed to the divide between ‘talking jobs and doing jobs’, with talking jobs either furloughed or being done online, and doing jobs – typically more those of what are being called ‘key workers’ putting people much more at risk and in difficult situations. The latter too frequently occupying roles that have lower pay, and can be prone to outsourcing and less secure employment. A bigger societal question raised by the pandemic and the recognition of key workers is how, from now on, the importance, social value and greater risks taken by such workers is recognised and properly rewarded in terms of pay?

The scale of the perversity of rewards in relation to the social value of work was revealed in 2009 by a NEF report called A Bit Rich? It compared the relationship between pay and the social importance of their work for high paid bankers, tax accountants and advertising executives on one hand, and for hospital cleaners, recycling workers and child care workers. Where the former were concerned, they destroyed more value than they created, with ratios varying from City bankers destroying £7 of social value for every pound in value they generated, to a staggering £47 : £1 negative ratio for tax accountants. Conversely, hospital cleaners generated £10 of social value for every £1 they were paid, for child care workers the positive ratio was between £7-£9.50 : £1, and for waste recycling workers £12 – £1.

Without other changes, too, under current circumstances, a big shift to home working is likely to place a disproportionate burden on women.

Rethinking the shape of the economy

Changes to the nature of work and the security of livelihoods are linked integrally to the wider shape and health of the economy.

Prof Richard Murphy, believed that ‘a good chunk of our economy’ is set to be wiped out with costs likely passed onto the commercial rented sector. However, he sees this as an opportunity to revisit the legal purpose of the corporation, reduced in recent years by financialisation to a purpose only of making money. Early corporations were given charters in return for performing specific, socially and economically useful functions. Now, he argues, is the time to re-establish the purpose of the corporation as an organisation within society to build resilience and focus on core, social foundations. The crisis has revealed the degree to which the whole economy sits on public foundations, meaning, “We’ll rediscover the priorities of society.” Companies will need support and will need, in return, to be far more accountable to the public, with mandates, protected by regulation, for a quid pro quo with society about the contributions they make to our overall resilience as employers, providers of goods and services, in paying their taxes and as part of the community.

Ann Pettifor of Prime Economics, which has warned of the return of austerity, argues that restoring public finances to health means primarily creating jobs which generate income, including tax revenues, and that well-paid jobs generate more tax revenues than insecure, low- paid jobs. And, public investment has a major role to play in the creation of those jobs. In the UK, in an attempt to prepare opinion for the withdrawal of the furlough, employment support scheme, there was political spin against companies becoming ‘addicted to state support’. But, given the demonstrable reality of how businesses do depend more broadly on public infrastructure, and support during repeated economic crises, that could be seen as being like saying businesses are addicted to transport, legal, education & health systems too. The fact of the economy resting on public foundations, and therefore having a responsibility to that public, is a fact too often ignored.

Differently again, in terms of shifting the focus of economies from debt-fuelled over consumption, to economies of mutual care, greater equality and well-being, the experience of lockdown has redirected the energies of many toward more home food preparation and self-entertainment. Consumerism has been put, to a significant extant, been paused. In an attempt to manage demand and assure access to essential goods and services, major retailers launched a campaign to ‘Only buy what you need’. In the context of aggregate overconsumption in all relatively wealthy societies, this sets a precedent and could become a more equitable rule to run economies by.

Once it was the case, especially in more neoliberal economies, that nothing happened unless the markets approved. Now a consensus is growing that the well-being and health of people comes first.

Our next crisis conversation looks at the role of finance and banking.