As many look to ‘build back better’ from the economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic, there are competing voices arguing on the one hand to restart old consumption habits, and on the other to ‘reset’ to more sustainable ways of living with less focus on consumerism and more on quality of life. Which path societies take will be strongly influenced by the amount and nature of advertising. And, there are new calls to apply the lessons learned from the successful campaign to end tobacco advertising to ‘high carbon’ products and lifestyles, and to ‘stop adverts fuelling the climate emergency‘. Urgent changes to the advertising industry are now coming into view as one of the important ways to create the conditions for rapid transition.

One of the mechanisms for driving consumption and encouraging us to ‘shop until we drop’ is the advertising industry. Not only has it shaped our purchasing habits, but it has changed with them and now includes online ads as well as TV, radio, print and physical advertising such as billboards, increasingly including energy-hungry digital versions of them. In 2020, total media ad spending worldwide is expected to reach $691.7 billion, up by 7.0% from 2019, despite the pandemic. It’s a vast sum of money and to put that into perspective, it is more than the massive infrastructure investment programme China used to get out of recession after the 2008 financial crisis. By 2009, China was growing 8.7% again thanks to giant public works projects—six-lane highways, bridges, ports, new skyscraper-strewn commercial centres. It is more than the $600 billion Federal Reserve lending fund set aside by the US for medium sized firms to combat the current economic crisis. It is also 4.5 times the $153 billion spent on development assistance in 2018 by all 30 members of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee.

In the face of such wealth, changing consumption patterns can seem daunting, but there are many examples of how bans on advertising have systematically changed behaviour and actually improved public health. Advertising is powerful and imprecise, because we respond to what we see and hear in a complex, invisible and sometimes unpredictable way. We also may not realise we are being influenced and people pride themselves on being more savvy consumers. With this in mind, campaigners and policymakers have worked together on many occasions to stop advertising affecting vulnerable communities, such as children.

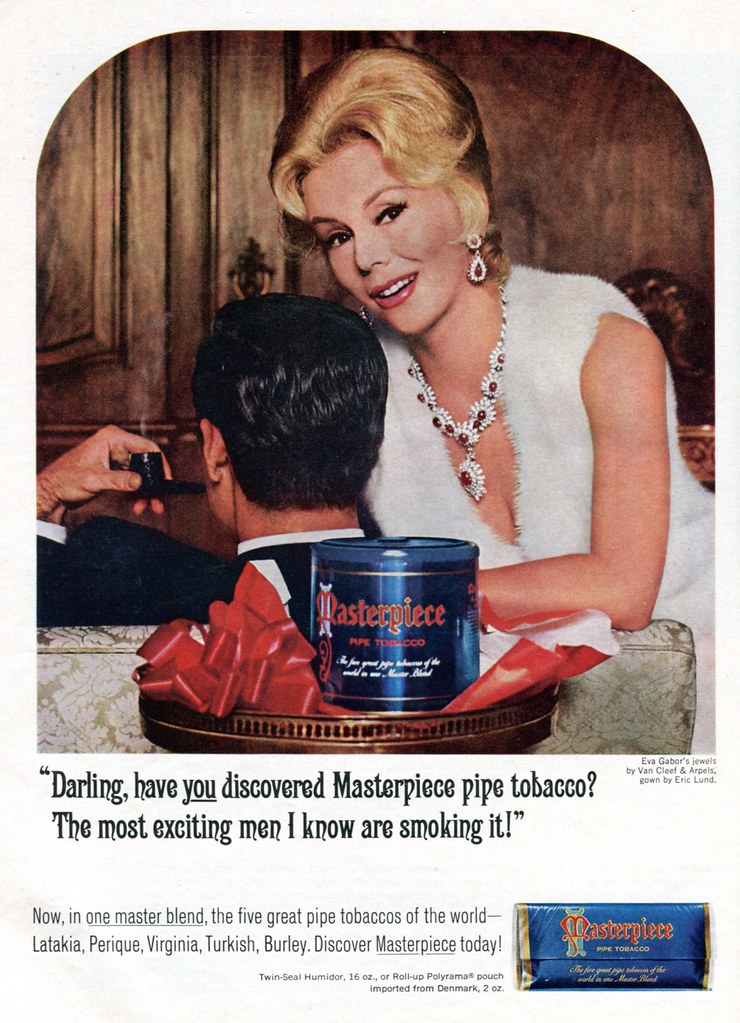

Once the huge public health impact of tobacco became clear – 100 million people died as a result of tobacco use in the 21st century and the figure for this century is expected to reach 1 billion – campaigners have worked tirelessly to ban its promotion. The attempt to ban tobacco advertising took 40 years from the first evidence of its damage to our health to passing into law. For years the tobacco industry resisted calls to end advertising arguing, for example, that it didn’t increase smoking but merely encouraged people to switch brands. But there was evidence to the contrary as early as 1975, showing how advertising increased smoking, and this evidence accumulated in subsequent decades. Television advertising of tobacco products was banned in the UK as early as 1965 and wider advertising bans began to emerge in Scandinavia, where any advertising to children under 12 today is illegal. Finland – once with the highest number of smokers in Europe – halved the rate of 14-year-old boys smoking within two years of their ban in the 1970s. Tobacco promotion in the UK was finally banned in 2003 and smoking indoors in public places in 2007, as was the case widely across Europe. Whereas it may take years to embolden decision makers to pass laws, actual behaviour itself can then change overnight. As we’ve reported in another story of change, when in March 2004, overnight Ireland banned smoking in the workplace there were warnings that the new rules would be ignored. In fact, it changed life forever in Dublin’s pubs, offices and factories.

Today’s campaigners – such as the UK’s recent “Badvertising” campaign – are using the same arguments to focus on other advertising of products that are a threat to our environment, health and wellbeing, such as gas-guzzling 4x4s, also known as SUVs.

They draw direct comparisons between tobacco bans and the ending of SUV advertising, using the well known dangers of smoking to make air pollution a personal and public health issue. For climate and health campaigners today there are valuable lessons to be learned from the fight against tobacco promotion. Both tobacco smoke and car exhausts contain similar toxins that directly threaten human health. Underlying health conditions mean that lower income households are worse affected than richer households by the effects of tobacco and air pollution from vehicles, and hence more vulnerable too in the face of health crises like the coronavirus pandemic.

We are in a stronger position today to speed up this cycle and make it part of a rapid transition. The internet spreads ideas quickly, enabling more transparency and better coordination by campaigners; US followers have already picked up on the Badvertising campaign and are pushing for it to happen in the US too. People are also more aware of the influence of advertising and are perhaps more willing to respond to suggestions to limit its effect.

Junk food is one area where campaigners are focusing attention more quickly and effectively on advertisers and their responsibility for poor health – and particularly obesity in children. In 2020, the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca banned the sale of sugary drinks and high-calorie snack foods to children – a measure aimed at curbing obesity that places these products in the same category as tobacco and alcohol. In 2018, Transport for London (TfL) implemented a similar ban on unhealthy food advertising across its whole network, including the underground metro system, buses, bus stops and taxis. The policy was voted on by the Greater London Authority – a democratic, elected body – whose consultation on the proposals found that 82% of Londoners supported the ban. The UK government is now set to implement strict rules on how junk food is advertised and sold across the country, with restrictions such as a ban on online adverts and TV commercials before the 9pm television watershed.

These examples show how change can happen even in the most intransigent places, where the power balance is extremely unequal. Powerful industries are not easily going to give up potential revenue, as the struggle to end tobacco advertising demonstrated. But strong messages of public health can prove overwhelming – even for the biggest firms. Using the power of advertising against itself with the support of scientific evidence has proven effective in the past and can be so in the future too.

The length of time it took to get the tobacco ban implemented, shows the power of the opposition and illustrates that campaigners cannot rely on evidence alone to win their argument. In order to bring politicians on side to change policy, it is essential to garner public opinion, which means changing hearts as well as minds. The tobacco industry was successful in spreading doubt, paying for endless research and harnessing apparently creditable bodies to muddy the waters, and discrediting those in opposition.

It was not until 2006, that a US district judge ruled that tobacco companies had “devised and executed a scheme to defraud consumers … about the hazards of cigarettes, hazards that their own internal company documents proved that they had known about since the 1950s.”17 They were found guilty under the Racketeer Influenced Corrupt Organisations Act. In the meantime, their actions led to four decades of delay, while the industry spread doubt about epidemiological research showing the dangers of secondhand smoke. They also spread the idea of ‘sick building syndrome’ – to distract attention and provide themselves with an alternative explanation for health findings other than the effect of secondhand smoke.

Yet strong campaigners working with solid policymakers with genuine good intentions can make change happen. No one denies the grip Mexico’s drinks industry has on the country’s population. Mexicans drink 163 litres of soft drink a year per head – the most in the world – and consumption starts young. A survey by El Poder del Consumidor – a consumer advocacy group and drinks industry critic – found 70% of schoolchildren in a poor region of Guerrero state reported having soda for breakfast. Some 73% of the population in Mexico is considered overweight, and related diseases such as diabetes are rife. “When you go to these communities, what you find is junk food. There’s no access to clean drinking water,” said Alejandro Calvillo, director of El Poder del Consumidor.

In an earlier case study we looked specifically at outdoor advertising and how local people campaigned successfully using existing local laws to reduce or remove them entirely. Many US states strongly control public advertising and four have banned billboards completely. In Paris, rules were introduced to reduce advertising on the city’s streets by 30 per cent and cap the size of hoardings. Moreover, no adverts are allowed within 50 metres of school gates. The Indian city of Chennai banned billboard advertising completely, and Grenoble in France recently banned commercial advertising in public places in the city’s streets, to enhance opportunities for non-commercial expression. Several hundred advertising signs were replaced by tree planting and community noticeboards.

Communities in the city of Bristol, England collectively organised recently against the onslaught of bright, invasive LCD billboards, which were popping up across the city, dominating the area and causing light pollution and energy wastage. Adblock Bristol was formed in 2017 to help residents object to planning applications for new digital advertising screens. This has opened up a conversation in the city with the local council about the role of public space, consumerism, advertising and climate breakdown. So far, the group has stopped 25 planning applications for large digital screens and over 50 smaller advertising screens. Similar groups have now been established in other British cities – Birmingham, Cardiff, Leeds and Exeter – which are now forming the Adfree Cities national network.

Makers and producers have always used advertising to sell their wares, promoting their favourable qualities and playing down their negative points. But sending a message about a product to a wide audience in order to encourage the sale of additional, extra or luxury items rather than essentials grew hugely in the 20th Century. As with many economic and social changes, global war made a difference.

Advertising is a large part of the broader public relations industry which has its roots in war time propaganda. Often referred to as the father of this industry is a man called Edward Bernays, who worked for the Committee on Public Information, a body for official propaganda, under Woodrow Wilson’s administration during the First World War. Bernays wrote that. ‘Those who manipulate the unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power. We are governed, our minds moulded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested largely by men we have never heard of.’ The founder in 1953 of one the world’s largest public relations companies, Burson Marsteller, Harold Burson, later cited Bernays as one of his great influences.

At the same time as Bernays was active, the British Secretary of State for War in 1914 recruited the services of the publicist Hedley Le Bas of the Caxton Publishing Company to drum up support for their recruitment campaigns using emotional appeals and imagery. These advertising firms in turn learned from the success of this campaign to bring patriotism into their products as often as possible.

For example, the razor blade company Gillette changed men’s shaving habits overnight by linking being clean-shaven with being on the right side of the war. Beards, which were entirely normal at the time, prevented men from wearing gas masks and held lice. But shaving had until then been done by barbers with a cut-throat blade – something more DIY had to be used in the trenches. King C Gillette had patented the safety razor in 1904 and struck a deal with the US Army that saw every American soldier sent off to Europe with a safety razor in his backpack. The troops of other nations then adopted this new practice with gusto. Gillette backed up its monopoly with the emotional tag lines describing clean-shaven soldiers as ‘Clean Fighters, fighting for clean ideals’.

In the 1930s, tobacco was marketed as healthy with doctors used to endorse cigarettes up until the early 1950s – and the brand Chesterfield was allowed to run adverts in the New York State Journal of Medicine, describing their product as: “just as pure as the water you drink … and practically untouched by human hands.” In 1939, Tobacco misuse and lung carcinoma, by Franz Hermann Muller of the University of Cologne, was the first major report to find a strong link between smoking and lung cancer, but the context of this report as a Nazi concern about damage to the Ayran race, made its findings toxic to the rest of the world.

In the UK, the Royal College of Physicians’ landmark report, Smoking and Health enabled a new reforming government and a Television Act of parliament. The tobacco companies hit back with a covert campaign, mainly in the USA, to spread doubt about the scientific research and took a series of legal actions to slow the pace of change. Warnings appeared on packets of cigarettes, but tobacco advertising money moved to sports sponsorship – a highly successful move that lasted another couple of decades. Arguments about governments’ reliance on tax revenue from tobacco spread further concern and confusion. Nevertheless, in Scandinavia in the mid-1970s, public spaces and institutions began to adopt policies against tobacco advertising – and Sweden still leads the charge today, with strict bans on smoking in public places – even outdoors – and the aim of being tobacco-free by 2025.

The tide started to turn against junk food throughout the 21st century, as health impacts start to mount up. In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) published the recommendation that the “overall policy objective [of an advertising ban] should be to reduce both the exposure of children to, and the power of, marketing of foods high in saturated fats, trans-fatty acids, free sugars, or salt”. The medical literature has since regularly called for restrictions on advertising, suggesting that the marketing of junk food and beverages is associated with increasing obesity rates, and that advertising is especially effective among children.

It is perhaps the impacts on children – seen as blameless consumers who frequently have not chosen to consume – that have proven effective in shifting policymakers from condemnation alone into taking action. Good research, clear messaging and believable people delivering it consistently all helped, but changing a law and banning an activity to protect children is a fail-safe method for politicians worried about public opinion. This was the case in Sweden, where advertising bans are aimed specifically at children, because of their inability to differentiate between fiction and reality. The recently announced ban in the UK on junk food advertising to children is following the same reasoning.

Having strong evidence on your side delivered clearly by trusted experts is also an enabling factor. One turning point in the battle against propaganda from the tobacco industry in the UK was the involvement of the doctors’ trade union, the British Medical Association (BMA), which shows the importance of getting credible and influential supporters on side. This crucial milestone brought the people the public trusted most – their family doctor – into direct confrontation with the tobacco industry. The Action for Smoking and Health (ASH), which was set up in 1971, under the wings of the Royal College of Physicians, was led from 1979 by David Simpson, who had previously won a Nobel Prize for his previous employer Amnesty International. Simpson described the impact of the support of the BMA as “like the Americans intervening in the Second World War”.

In 2017, an article in the Lancet, the leading British medical journal, featured yet another major study showing that climate change is a growing health hazard. Its author, Simon Dalby of Wilfrid Laurier University asks why we don’t use advertising restrictions for climate change in the same way that we have with other public health hazards like smoking. The study revealed that hundreds of millions of people around the world are already suffering due to climate change. Infectious diseases are spreading faster due to warmer temperatures, hunger and malnourishment is worsening, allergy seasons are getting longer and sometimes it’s simply too hot for farmers to tend to their crops. He suggests we treat climate change as a health problem rather than an environmental one.