Update

Since publishing this story of change, we have seen an interesting critique of the original paper that underpins much of the narrative, ‘The Long-run Poverty and Gender Impacts of Mobile Money’ written by US-based economists Tavneet Suri and William Jack, and published in the prestigious journal Science. The critique, entitled ‘Is Fin-tech the New Panacea for Poverty Alleviation and Local Development?’ (Bateman, Duvendack, and Loubere, 2019), claims the article contains a worrying number of omissions, errors, inconsistencies, and that it also employs flawed methodologies. It lays out concerns that it legitimises and strengthens a false narrative of the role that fin-tech can play in poverty alleviation and development, with potentially devastating consequences for the global poor. We think it is important to add this to the case study to allow readers to explore it fully, and to encourage discussion and wider dissemination of the debate.

With regard to M-Pesa in particular, the concerns raised are as follows:

Micro enterprises in very difficult to run profitably in Kenya and many fail causing additional poverty. Could M-Pesa be encouraging people to take risks they would not otherwise have taken?

These new microenterprises also take market share from existing businesses in an environment where demand is not very elastic and hyper competition is not necessarily a useful force.

The paper lauds the reported rise in client incomes and savings, but fails to measure or comment on increases in levels of client debt. This is a big issue in a poor country and could be storing up problems for the future.

Safaricom, which owns M-Pesa, is owned 35% by the Kenyan government and over 40% by the UK firm Vodafone through its South African subsidiary. This company is highly profitable and pays strong dividends. There are claims that this form of extractive capitalism is no different from industries that take physical resources and is reminiscent of colonial attitudes and activities.

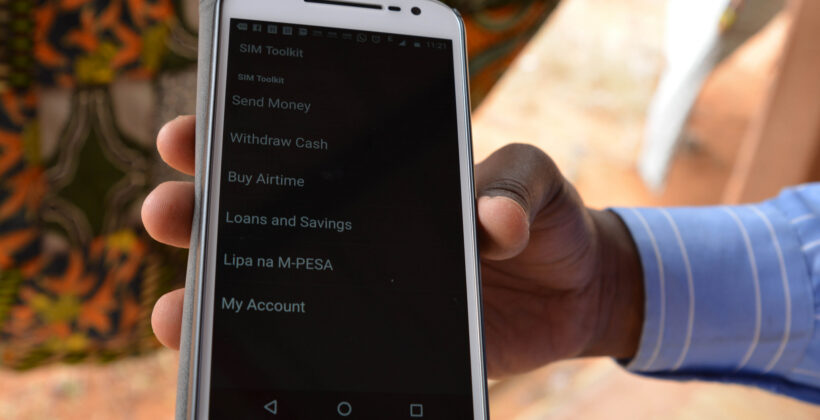

Financial exclusion is a large part of the jigsaw of global poverty. But in just over 6 years an additional 800 million people around the world gained access to basic banking services. It’s a glimpse of how quickly economic infrastructure can change. Part of that revolution can be found, quite literally, in the hands of people in Kenya.

A mobile phone payment system was set up in the country just over a decade ago that has revolutionised African banking, and given access to financial services to millions of the poorest people for the first time. M-Pesa (M-money in Swahili) began as a simple method of texting small payments between users making microfinance repayments. Today it services 30 million users across 10 countries, partnering with traditional banks to offer further services such as international transfers, loans and health provision. M-Pesa is credited with some impressive achievements – from making economic activity in rural areas easier and stimulating entrepreneurialism, to changing the whole banking system. It has also generated a range of unexpected social benefits.

The idea came originally from the communications company Vodafone and was developed with funding from the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID)’s Challenge Fund. By reducing the costs associated with handling cash, they planned to enable microfinance providers to lower their interest rates and widen access to loans. But pilot testing with Vodafone’s mobile operator Safaricom revealed that people wanted to use M-Pesa in all sorts of ways: businesses used it to pay other business, or as an overnight safe; and people used it to transfer airtime as currency to relatives and to people outside the pilot areas. Safaricom shifted direction and launched M-Pesa as a general money-transfer scheme.

The system works by getting users to sign up and pay cash into the system via one of Safaricom’s 130,000 agents (typically someone in a corner shop selling airtime). They credit the money to your M-Pesa account and you can then withdraw cash from any agent, who checks you have sufficient funds before debiting your account. You can also transfer money directly to others. Sending cash this way is quicker, safer and easier than carrying bundles of money in person, or asking others to carry it for you. This is particularly useful in a country where many workers in cities send money back home to their families in rural villages and for women, who are more vulnerable to personal theft.

Today the scale of the operation is impressive: Safaricom reported over 6 billion M-Pesa transactions in 2016 and in its 2017 Annual Report registers £1.39 billion worth of “social impact”. It has also started a charitable foundation with some of the profits made.

The M-Pesa model is interesting because of the speed with which it grew; its ability to reach poor populations that most innovations bypass completely; and the accompanying social benefits it has brought. These include better personal security, faster response to emergencies, reduced opportunity for corruption and more time for productive activities.

Choosing to base payment transfers on simple texting technology made the system cheap to install and available to anyone with a mobile phone, which meant it could grow fast. Many people in developing nations have jumped straight to mobile services without ever owning a landline. Creative, speedy and safe new services are therefore instantly available even to the poorest. Between 2008 and 2011 alone, the percentage of people living on less than $1.25 a day who used M-Pesa rose from below 20% to 72%. In Kenya today, over 80% of adults own a mobile and more have access to one.

One M-Pesa service allows users to fundraise for a variety of purposes, including medical needs, education, and disaster relief. Family networks can help absorb the economic shock of an emergency better by lending or giving money immediately via their phones. In times of natural disaster, climate change and war, mobile money can be a lifeline as populations are forced to move at short notice and leave their belongings behind. Digital humanitarian cash transfers and affordable international remittances give refugees safe and convenient ways to meet their immediate needs. Governments could be putting these systems in place now to help with responsiveness in the future.

Meanwhile, in more stable places, smallholder farmers can use the service to access credit and maximise supply chain efficiencies. This helps bridge the divide between city and county. It also cuts down on corruption by reducing the opportunity and access to funds; when users transfer money directly to each other there is simply less cash floating around. Cash is so much easier to steal or embezzle – and it is the poorest who suffer most from corruption, because they are usually forced to use cash more.

The media has widely praised M-Pesa for empowering Kenyan entrepreneurs and it is true that many small companies – including sustainable and community-led projects – rely on the system for nearly all transactions. Micro-grids set up near Lake Victoria take payments via M-Pesa to provide solar generated electricity directly to local communities. Subsistence farmers now have better access to markets, using refrigeration to keep produce fresh for longer. And it has provided their communities with safe, clean cooking – inhalation of smoke from cooking fires is a huge health problem in Africa and cutting firewood contributes to deforestation.

Many small business owners in Kenya are women, who often travel long distances to buy stock or make a sale. M-Pesa enables them to make transactions remotely, without the need to close up shop, and perhaps take children out of school. This means increased time for education and business development, children can stay in school, and women no longer have to worry about being robbed as they travel with bundles of cash. One study showed how mobile money payments also improved community trust between fishermen and local women wholesalers by enabling faster and more consistent payments.

This technology is already being replicated in other countries and has proved particularly effective in situations of national emergency. In nearby Zimbabwe, mobile payments replaced cash after the fall of their currency. The country adopted the US dollar in an attempt to stabilise the economy, but insufficient notes and coins were available and long queues outside banks ensued. Mobile phone banking came to the rescue and today over 80% of the country’s transactions are made digitally. With more research and technology sharing, new and productive uses for handheld mobile technology will undoubtedly arise that could prove useful in climate related emergencies.

One unexpected outcome has been the birth of the M-Pesa foundation, which uses profits from the service to focus on large scale, long term projects in the areas of education, environment and health. Projects funded include the fencing and reforestation of the vast Mau Eburu forest, and planting an indigenous tree buffer zone called “The Nairobi Greenline” between the Nairobi National game reserve and the capital city. Through partnerships with existing projects, it claims to have reached more than four million Kenyans through programmes to reduce poverty, increase access to high quality education, and improve maternal health care and access to clean water.

Access to banking and credit for the majority was limited in Kenya and transporting cash was both risky and slow. The rural population is still highly dependent on agriculture, which is often at subsistence level. This means they are vulnerable to shocks – economic, social and climatic – and rely on family support from outside the country or from workers in the cities to help them through hard times.

Women were particularly at risk when carrying cash; many run shops, stalls and roadside businesses that rely entirely on cash. Non-cash options were limited to: expensive services, such as MoneyGram, Postapay or Western Union; ferrying money in unaccompanied parcels via bus companies (these are open to being stolen or interfered with) or travelling long distances in person with cash on public buses at the risk of being robbed.

Restricted access to cash prevents businesses from growing. In unstable states and countries where people distrust the police and authorities, a lack of redress from theft, violence and corruption can also act as a brake on community development and cohesion. This effect is particularly strong for women, who already suffer from a higher level of deprivation. Innovations that free up women to look after their own and their children’s health and education, have a better chance of bringing about long-term economic and societal change.

This transition came about rapidly because different actors along the way responded effectively to the challenge at hand and because there was a huge gap in the market. As far back as 2002, researchers at Gamos and the Commonwealth Telecommunications Organisation had discovered that people were using airtime as a proxy for currency, transferring credits between themselves in return for services.

Meanwhile, Vodafone’s Head of Global Payments, Nick Hughes, had been tasked with helping the company to understand its role in addressing the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). He was considering ways to use mobile phone banking to widen access to financial systems but his board was unable to support product development that was not profitable. Funding from the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID), brought the two together by offering match funding through their Challenge Fund – established specifically to finance public-private partnership projects that would improve access to financial services. They decided to look for a way to improve systems for repaying microfinance loans.

The development of M-Pesa looks straightforward in hindsight, but it was far from easy. It took tenacity, vision and flexibility. Mobile phone banking did not come under financial regulation in Kenya, which meant the banking sector was concerned it could be used to launder money. So the development team at Vodafone/Safaricom were forced to go ahead without a financial partner. Once the pilot proved successful, the Central Bank of Kenya agreed to give them a special licence. Under this, all customer funds had to be deposited in a regulated financial institution with interest on deposits going to a not-for-profit trust and the e-float could not be invested.

The software to make such a system work did not exist and it needed to work on the most basic models of mobile phones. Smartphones were a rarity in 2007 and even in 2018 they account for just 20% of Kenya’s mobile phone ownership. The British company Sagentia worked with local developers and users to create a platform that could be used with minimal training at low cost.

The last piece in the jigsaw was the strong need to move small amounts of money around – both within a large country with a relatively poor road and rail system, and internationally from the diaspora back home. Traditionally in Kenya many people work long distances from home and send money back to their families. Using the simple marketing message ‘Send Money Home’, M-Pesa filled a gap that was crying out for a secure and cheap service. Once trust in the system was established, it grew quickly and additional services were developed.