The scandal of food waste is generating headlines and highlights a broken relationship with what we eat. But interest in growing our own is increasing, which could both bring a healthier way to relate to food and be part of the jigsaw of making the rapid transition towards preventing climate breakdown and protecting ourselves from it. History suggests that under certain circumstances, such changes can happen very quickly.

In the UK, the phenomenon of growing vegetables on an allotment – a piece of community land shared between a number of individuals – is part of the national landscape, bringing pleasure and fresh homegrown vegetables to households without large gardens. But there are times in the country’s history when gardening became a matter of serious food production for survival and to reduce the threat of shortages or dependence on expensive imported food. In both the First and Second World Wars, the British government faced food shortages as imports were blocked, and turned to its people to grow their own food. This policy worked both times, achieving results quickly and at scale, dramatically raising the nation’s relative food self-reliance, and sparking simultaneous social change.

Today, the prevailing assumption has been that global markets can be turned to, and will always provide. But several factors are causing that approach to be revised. A rising awareness of the environmental impact and carbon emissions of long-distance food trade is combining with a shifting geopolitics of food. Extreme weather events linked to climate breakdown not only cause failed crops but a rise in ‘food nationalism’ – countries prioritising production for local consumption over export. This is complicated by the phenomenon of ‘land grabbing’ – whereby countries and corporations effectively take control of the farmland of other, often poorer nations. A combination of these factors can raise the prices and reduce the availability of food from international markets, making food security once again an issue, even for relatively wealthy countries.

There are well-established health and well-being advantages to growing your own food. But these historical experiences might also point to ways to reduce the environmental impact of food growing, and be one ingredient to ease the rapid transition to lower carbon food production.

The allotments revolution created in the First World War started as an emergency measure to mitigate food shortages. German U-boats were successfully sinking ships that were importing food and the agriculture minister, the Earl of Crawford, realised how quickly the nation’s reserves were being run down and the danger of food running out. The resulting Cultivation of Lands Order 1916 gave county councils the right to take over waste land or abandoned land, without the consent or even knowledge of its owners, and use it to grow food. Crawford had been nervous that the order would outrage people, but in fact the local authorities were overwhelmed with demand from people applying to turn specific pieces of land into allotments, or to take over part of the new allotments themselves. It was a phenomenon that the press called ‘allotmentitis’, which described the addiction that ordinary men and women- whose role caused particular comment – had to working in the open air growing food. There were 440,000 allotments in the UK at the outbreak of the First World War in 2014, but just three years later, this had leapt to 1.5 million.Even the Prime Minister David Lloyd George let it be known that he was growing potatoes at home – and the Archbishop of Canterbury issued a special letter allowing people to work on allotments on Sundays.

The idea was rejuvenated in the Second World War under the promotional title “Dig for Victory” as part of a massive propaganda campaign to ensure that people had enough to eat, and that morale was kept high. When America’s involvement in the war became inescapable there was a similar campaign pioneered by Eleanor Roosevelt, the President’s wife, something which was directly echoed in 2009 when Michelle Obama established a kitchen garden in the grounds of the White House. And, in the wake of the financial crisis of 2007 – 2008, there was an upsurge of the urban growing movement, often in some of the economically worst hit cities, like Detroit, as a direct response to hardship and poor access to good food.

Back in Britain as the war was waged, people across the country were encouraged to grow their own food in times of harsh rationing and few imports. Open spaces everywhere were transformed into allotments, from domestic gardens to public parks. By 1942, half the civilian population was part of the nation’s “Garden Front”, and ten thousand square miles of land had been ploughed and planted. School playing fields, public gardens and factory courtyards were all transformed into allotments. It was important that privileged people and places were seen to participate: the moat at the Tower of London was given over to vegetable patches, and even the Royal Family sacrificed their rose beds for growing onions.

Food production is a subject of widespread discussion today, with concerns about food safety, genetic modification, food security, chemical use, food waste, food miles, and soil degradation all in the headlines. Both the allotment and Dig For Victory campaigns show how change can take place quickly and on a huge scale, given the right conditions: a sense of emergency, the need to pull together to overcome a dangerous threat to life, and a government ready to regulate and educate in support of a “home growing” policy.

A sense of emergency has been created by a series of UN and government reports on climate change and its effects on food production, and on soil degradation threatens to undermine our agriculture. Of course, it is easier to mobilise a population against a common enemy than against a catastrophe such as climate change which only sporadically reveals its effects to some, or against the profligacy of our own behaviour. How can we strike a balance between generating the urgency needed to change behaviour rapidly in a way which is culturally resonant today, compare to the public information campaigns that were successful in two world wars? In wartime Britain, the government gave councils the power to take over land or stipulate its use; could councils who have issued a climate emergency do the same, what issues would this raise and how would they be managed? Would citizens’ assemblies play a role, for example? Are there uncontroversial possibilities for councils to use their own and more public land to demonstrate possibilities, and could this be part of broader programmes to advance public health and well being?

It is important to recognise that the use of land changes all the time, depending on government policies, global economics and other external forces. The UK was wholly self-sufficient in food before the start of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century. Self-sufficiency sank to a record low of 30% before the Second World War, rose again during the war, but production drifted back down afterwards. In 2009, UK production stood at 62% and most imports were still plants that have to be grown in hotter countries such as bananas, oranges, tomatoes, tea and coffee. In 2017, 50% of the total food consumed in the UK had its origins here, with 30% from elsewhere in the EU.

And things are shifting again. A poll commissioned by City of London in 2012 reported that nearly a third of British adults grew their own food, with many believing it to be healthier. One in six adults had started growing their own food in the previous four years and 51% of those surveyed said they would consider growing their own fruit, vegetables and herbs – or growing more – if food prices rose further. Farmers markets are a normal part of the urban landscape, and there are growing numbers of individual companies supplying local food to niche markets and retailers. Veg box schemes have also grown in popularity, offering local and/or organically grown produce. Outspoken business leaders, such as Guy Singh-Watson from Riverford Organic in the UK have also taken on the role of campaigning for local, organic production.

Then there is the inspiring example of the town of Todmorden in Yorkshire, where two women started, in 2008, to use urban unused space more productively by planting veg wherever they could – on roundabouts, outside the police station and in supermarket car parks. The vegetable plots are the most visible sign of their amazing plan to make Todmorden the first town in the country that is self-sufficient in food. People have come from all over the world to learn from this scheme, which was started by volunteers with no funds; perhaps the UK government could use it as a model for scaling up quickly across the nation? Others cities have seen “guerilla gardening” efforts to use land productively, including London, Venice and Auckland.

In 2015, there were 300,000 council-owned allotments in Britain, with an additional 10% remaining on private land or newly created by organisations such as the National Trust and British Waterways. And demand still outstrips supply, with more than 90,000 people on waiting lists to get their own patch of land to grow vegetables.

The month of November 1916, the mid-point of the First World War, was a worrying one for the embattled allies. The disastrous Battle of the Somme had seen 95,000 British and empire dead, faith in the Prime Minister Asquith was dwindling, and the Russian government had fallen. The head of the Navy, Sir John Jellicoe, was engaged in bitter disagreements about whether to introduce the same convoy system that had been used so successfully in the Napoleonic Wars. By the spring or early summer, before the next harvest, the Agriculture Minister, Crawford, could see perfectly clearly – just as his officials could – there was a serious danger that the nation would run out of food. In the first few months of 1917, shipping losses rose to over 600,000 tons a month, which was the figure the German High Command believed would starve Britain into submission within six months. Wheat supplies dropped to just six weeks’ worth. There was panic buying of potatoes and nervous memories of the Irish Potato Famine only seven decades before. People were queuing for hours to get enough to feed their families and there was an eruption of public anger. Crawford’s allotment plan helped people to help themselves and enabled public action in a time of fear.

In the second world war, the UK’s dependence on imports from North America once again proved our Achilles heel, plus the Merchant Navy was needed to carry troops and munitions, rather than food for civilians. The Dig for Victory campaign was set up in response to the Nazi’s threat to “starve Britain out”, by the head of the Agricultural Plans Branch of the Ministry of Food, Professor John Raeburn. It was spearheaded by Lord Woolton, Minister for Food until he left office in 1943, but Raeburn continued to run the programme until the end of the war.

He then went back to Oxford University as a senior research officer, but played a leading role in developing the landmark 1947 Agriculture Act, which reshaped farming in Britain. Annual price reviews fixed prices for the main crops – wheat, barley, oats, rye, potatoes and sugar beet – for 18 months ahead while prices for fatstock, milk and eggs were fixed between two and four years ahead. The experience of food shortages remained strong in the collective memory of the UK and continues to influence policy today.

Raeburn argued in favour of “rational thinking” in establishing agricultural policy, challenged the assumption that bigger was either better or more efficient in terms of measurable human outcomes and pleaded for the importance of agricultural research in overcoming poverty and disease. He argued that the past history of successes and failures in agrarian development and assistance should be re-examined for new lessons relevant to the modern world. He travelled and worked in several countries, keen to learn from others what worked best. Raeburn deplored the casual drift towards massive reliance on food imports and practised what he preached at home, feeding his family on the produce of their own garden.

The transition was able to happen so rapidly for a number of reasons in the case of both wars: our reliance on imported food created a feeling of being under siege and a fear of running out that brought people together; poverty meant people were keen to take advantage of free food; and strong, successful campaigning with a simple message was easy to communicate using public radio and posters.

The allotments of the First World War filled a gaping social need as well as a generating food production. Many British cities were dirty places with insanitary housing, few basic services and poor nutrition. Those growing veg on allotments had access to a healthier diet and formed new communities. Adding to concerns about British food stocks, the wheat harvest of 1916 was lower than usual and the potato crop in Scotland and parts of England failed. Food prices started rapidly increasing, making some items unaffordable for many people. People with allotments could make additional income; successful allotments could produce food to the value of £80 an acre – in the days when a hefty bag of potatoes cost 5d (about 2p). So allotments became a tool of poverty reduction.

Modern research backs up the historical evidence. A 2012 study by Newcastle University reported that allotments and community gardens can improve people’s quality of life in numerous ways. It can help to curb social exclusion, increase physical exercise, encourage a nutritious diet, support mental health, help people relax, teach new life skills, empower people, give individuals self‐esteem, reconnect people with the food they eat, educate citizens about healthy food and environmental stability, tackle CO2 emissions, reduce packaging, support more sustainable waste management, conserve biodiversity, facilitate social interaction, build cohesive communities, strengthen social ties and networks, secure our food supplies and even reduce perceptions of crime.

Food production also became part of women’s liberation, as many men from the farming industry joined the armed services, leaving the country in short supply of agricultural workers. In 1917 the Women’s Land Army was formed to provide extra voluntary labour, with ‘Land Girls’ replacing servicemen who had left the farms to fight. This disbanded after the war and reformed in June 1939. Women were initially asked to volunteer to serve in the Land Army, but from December 1941 could also be conscripted. At its peak in 1944, there were more than 80,000 women in the WLA. They worked on farms, in dairies, as ratcatchers, as foresters and also drained land to bring it into food production.

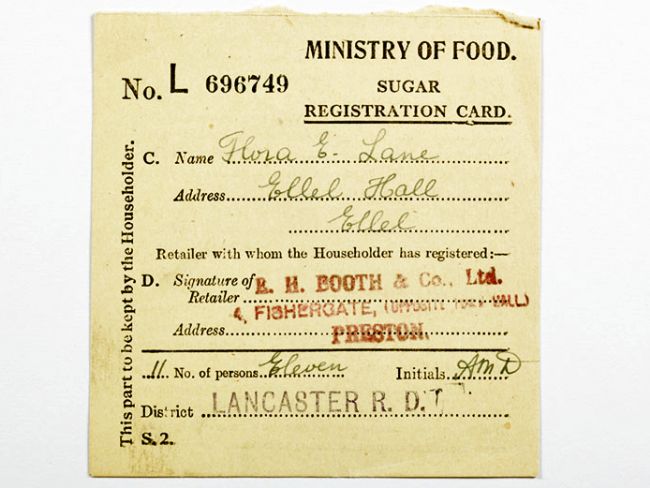

Land reallocation was successfully localised during both wars, leaving councils to carry out their own organisation. For example, in February 1917, a committee was formed in Preston, Lancashire, to secure 700 plots for allotments in the town’s parks and other public land for the growing of food. This increased to 1,845 by 1919. Alongside this, a scheme of voluntary rationing was promoted on 1 February 1917, with the aim of reducing the consumption of food in short supply, and to show how to avoid waste when cooking. Teachers in elementary schools took up the challenge and cookery centres were established in Preston.

The allowance under this scheme was based on three staples of the daily diet – bread, meat, and sugar. A food control office was then set up to fix the price of milk and butter. Shortages continued and although wealthier people could still afford food, malnutrition was seen in poor communities. To try to make things fairer, the government introduced rationing in 1918.

Successful propaganda played a huge role in making the transition work so quickly – particularly during the Dig For Victory campaign, although the First World War also featured an appeal to taking its slogan from the Defence of the Realm Act – prospective plot holders were encouraged to ‘DIG for DoRA’. The media was less diverse in 1939, with everyone listening to the BBC’s new Home Service; every Sunday an audience of 3.5 million tuned in to listen to Britain’s first celebrity gardener, Cecil Henry Middleton, give his gardening tips. Cartoon characters Captain Carrot and Potato Pete led the campaign with their own songs and recipe books. The campaign included iconic posters displayed in stations, shops and offices, leaflets, specially written songs and slogans, and even lists of recommended ‘food for free’ in the countryside. According to the Royal Horticultural Society there were nearly 1.4 million allotments in Britain by the end of the war, which produced 1.3m tonnes of produce. The government estimated that around 6,000 pigs were kept in gardens and backyards by 1945. In Scotland, 54,000 children in school helped to plant the potato harvest, even having time off school.

Dig For Victory Song

Dig! Dig! Dig!

And your muscles will grow big

Keep on pushing the spade

Don’t mind the worms

Just ignore their squirms

And when your back aches laugh for glee

Just keep on digging

Till we give our foes a wigging

Dig! Dig Dig! for Victory!