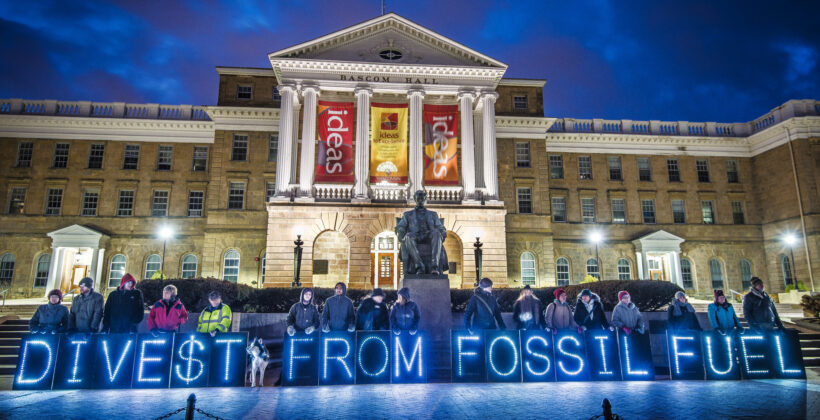

From the first known, active divestment from fossil fuels by the small Unity college in Portland, Maine, United States in 2012, in just six years the movement grew to reach its 1,000th divestment by late 2018. Divesting has now become the largest campaign of its kind, changing corporate behaviour and creating conditions for rapid transition.

When the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund announced in March 2019 that it would be selling some $7.5 billion of its oil and gas holdings – and for economic rather than moral reasons it took the shift to a whole new level. Norway’s $1 trillion Government Pension Fund has now joined more than a thousand other institutional investors totalling more than $8tn between them, who have made pledges to divest from fossil fuels. This signals a tipping point for the future of fossil fuel investments and a huge success for the divestment movement.

Norway is western Europe’s biggest oil and gas producer and uses its fund to invest the proceeds of the country’s oil industry. It currently owns $37bn of shares in oil companies such as BP, Shell and France’s Totalis, but is unlikely to divest quickly in these major players, because the country is still heavily committed to oil and gas extraction. Instead, it intends to sell shares it holds in riskier, small exploration and drilling companies. The fact that it has taken this decision as part of sensible portfolio planning, rather than to adopt a moral stance, shows the mindset of mainstream investors is changing and is no bad thing. We know that markets are not rational and that contagion can happen unexpectedly. Is this just one of the first ripples indicating an even bigger wave to come of mainstream divesting for economic reasons?

Non governmental organisations (NGOs) supporting divestment reported this as a huge breakthrough, but some also expressed disappointment that the fund was not divesting completely from fossil fuels. This is perhaps not surprising for a country whose economy is still strongly reliant on oil and gas. It has not yet indicated whether these funds will be moved into renewables, but it has expressed the desire to diversify into wind and solar energy.

Norway’s move illustrates a wider trend toward sophisticated and ethical investing, led mostly by investors in the EU and particularly in Nordic countries. The country’s much vaunted approach to environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) was driven largely by its Government Pension Fund. Since the fund was almost exclusively invested for the benefit of the next generation, they decided to develop an inter-generationally fair framework with integrated ESG principles.

Climate change has been a big issue for Nordic ethical screening in the past few years, but fossil fuel divestment has not happened as quickly as some might have expected. In fact, Norway has long been seen as passive in this area. As recently as 2013, an Oxford University report on “stranded assets” suggested that big “neutral” funds like those of Norway would readily soak up any shares sold by those divesting. A lot has changed in six years. It’s now a case of when when rather than if markets will shift.

It is particularly interesting that the government is – and says it is – diversifying for economic reasons, because they are too reliant on oil and gas. There is potential conflict at the heart of this: a government that has raised a huge pot of money by selling oil and gas looks foolish saying that using oil and gas is immoral. There is no sign they are trying to make such investments taboo.

The only fossil fuel that is becoming a pariah is coal – despite the vocal support of US president Donald Trump. This is because coal has an outsized influence on CO2 emissions, producing around 50% more CO2 per unit of energy than oil and over 60% more than gas.The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says at least 59% of coal power worldwide must be retired by 2030 to limit global warming to 1.5°C and many countries have set phase-out dates. So could oil and gas be next?

According to the UK NGO Carbon Tracker, which informs markets about the future risk of fossil fuel investments and viable alternatives, “The main impediments to change are now inertia and fossil fuel lobbying. Given that fossil fuels still make up 80% of primary energy supply this is still a powerful force.” A recent InfluenceMap report showed that the largest five stock market listed oil and gas companies spend nearly $200m (£153m) a year lobbying to delay, control or block policies to tackle climate change, while also spending about $195m a year on branding campaigns suggesting they support action against climate change.

In 2018, wind and solar met 45% of global electricity demand growth. The shifting of a major global fund will, however, resonate deeply and could affect market norms. It could have a particularly powerful effect on debt, because bank lending is risk averse, moving more slowly along well trodden paths and prefers the company of others. If institutional debt began to move away from fossil fuels, then transition to a renewable industry could happen much more quickly.

The global movement for divestment away from fossil fuels began in the US in 2011, inspired by earlier campaigns to force political change in South Africa in the 1970s by removing financial support for companies supporting apartheid. Student activists first launched campaigns in six universities to divest their endowments from coal, and by spring 2012 – and with the help of the campaigning organisation 350.org – this had broadened to a call to divest from all fossil fuels and invest in clean energy. A surge of students across the US and Europe took up the issue with their own institutions, many with success. Last year, the UK emerged as the world leader in university divestments, with over £80 billion divested.

A group of influential and wealthy US churches made pledges to divest between 2013 and 2016. Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical on the environment then led to a stream of Catholic institutions pledging to follow suit. In 2018, The Church of England announced its decision to divest from fossil fuel companies by 2023, should these companies not align themselves with the Paris Agreement or fail to take steps towards the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Divestment from fossil fuels is still a relatively niche activity. Despite the Paris Agreement calling for finance flows to be “consistent with a pathway toward low greenhouse gas emissions”, fossil fuels are still highly profitable and investment in oil and gas is still rising fast. According to a 2019 report from Banktrack.org, since the Paris Agreement was adopted (2016–2018), Canadian, Chinese, European, Japanese, and US banks have financed fossil fuels with $1.9 trillion, with levels rising each year. 2018 saw record global carbon dioxide emissions caused by a surge in world energy demand of 2.3%, which was mainly met by fossil fuels. The economic development of several lower income countries still relies on fossil fuels and making any shift away from this involves addressing global inequalities.

By contrast, the International Energy Agency (IEA) reported that although investment in renewable power accounted for two-thirds of power generation, it dropped 7% in 2017 to just $300 billion. One major reason for this is the huge imbalance of subsidies that have supported and continue to hold up fossil fuels. These favour investment in fossil fuels when demand increases, as it did in 2017-18. This was an unprecedented hot period and demand for cooling soared in India particularly.

The estimated value of global fossil-fuel consumption subsidies decreased by 15% to $260 billion in 2016, the lowest level since the International Energy Agency started tracking these subsidies in the World Energy Outlook (WEO) ten years ago. But it still dwarfs estimated government support to renewable energy: subsidies for renewables in power generation amounted to $140 billion in 2016. These figures also fail to include the invisible subsidy of environmental costs caused by fossil fuels, which were estimated by a 2017 World Development report at $5.3 trillion worldwide in 2015 (6.5% of global GDP. A 2017 report from several non-governmental organisations (NGOs) suggested that Group of 20 (G20) countries also provided four times as much public finance to fossil fuels as they did to clean energy.

Despite this, many renewable companies are thriving and their financial success will attract investors. It is vital that those divesting from fossil fuels redirect this funding into renewables if we are to see change at the speed and scale needed.

The divestment movement grew originally because rich institutions that wanted to be seen as taking the moral high ground were particularly open to pressure by their stakeholders. University students in the US pay highly for their education and make endowments as alumni, so their opinion counts. Similarly, churches rely on their followers for funding and are expected to be leaders in morality. UK students are now in a more similar position to that of their US counterparts – they are clients with financial clout.

Today, divestment is becoming normalised. Organisations such as 350.org and Shareaction drive bottom-up pressure from shareholders; and targets set by the Paris Agreement provide pressure from the top down. Meanwhile, a growing renewables industry offers viable alternatives that make moving out of fossil fuels less risky in the short term. The investment industry is awash with reports outlining threats to oil and gas firms: litigation, new legislation, dwindling resources, resources that are uneconomic to extract, evolving social norms and cheaper green technologies.

In the example of Norway, the fact that the government controls the fund enabled it to take this decision. It was supported by Norway’s central bank who suggested in 2017 that dropping oil and gas investments would be a good economic move. This can be seen as part of a trend of decarbonisation across the developed world, according to Engaged Tracking, a London-based independent advisor to the financial industry on climate risk. Senior Analyst, Constantine Pretenteris sees the exclusion of coal initially from portfolios as becoming increasingly popular and believes that there is widespread acceptance that our reliance on fossil fuels will end.

“But there is still far more talk than action: if you dig beneath the surface of many green funds you will find loopholes and reservations. For example, in order to divest, many funds stipulate that the firm must receive more than 20 or 30% of its income from fossil fuels, or from a particular fossil fuel. This excludes many of the largest greenhouse gas emitters, because their businesses are diverse.”

The UK-based financial thinktank specialising in energy transition, Carbontracker, also thinks markets are approaching a tipping point based on historical transitions. They quote:

“As a rule of thumb, incumbent sales will peak when the challenger gets to around 3% market share. Other energy transitions were similar. US horse numbers peaked when cars were 3% of their size. UK steam demand peaked when electricity was 3% of power supply. UK gas lighting demand peaked when electricity was 2% of lighting.”

Just 10 years ago, the world’s biggest companies by market capitalisation were oil and gas giants. Today, there is only 1 in the top 10. The rest are service providers such as Google, Apple and Amazon. This is not to say that they are as green as they say: these firms mostly claim carbon neutral status by offsetting, without reducing their emissions at source. They use vast amounts of energy and should take a lead in promoting and using renewables.

Renewables are fast-growing disruptive technologies that have reached critical mass and are poised to transform the global energy system. This makes traditional fossil fuel industries the risky option for the first time. The European electricity sector has already written off $150bn of stranded assets since 2008. These are generally accepted to be fossil fuel supply and generation resources which, at some time prior to the end of their economic life, are no longer able to earn an economic return because of transition to a low-carbon economy.

The legislative environment is also making it harder for investment in fossil fuels to continue – in particular in the EU, which has recently adopted legislation based on Article 173 of French law on Energy Transition and Green Growth. This is a legal innovation that has enjoyed international fame. The intention of legislators is to make large institutional investors aware of the risks that climate change poses to their portfolios, to better integrate Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance (ESG) dimensions in how they manage assets and to be able to explain this strategy to their end customers. This legislation has forced companies to disclose their carbon footprint and encouraged investors to treat the issue as a risk.