The relationship with ‘stuff’ in high-consuming, wealthy economies is set to change. From the European Union to the United States new laws are being developed to support the ‘right to repair’ to radically reduce waste, make things last longer and make them easier to repair. The giant economy of California is now the 18th state to make such a proposal.

The expectations we have about the lifetime of the things we buy have changed. Everyday items like washing machines, televisions and toasters have become transient visitors to our homes, which, once they break, are often cheaper to replace than repair. In our high consumption, disposable culture, the resource-draining turnover of consumer goods has become normalised, taken for granted and as a result, almost invisible.

Most people will be familiar with the nagging frustration when, just a year or two after spending several hundreds of pounds on a mobile phone, it slows right down and the battery drains to zero in minutes. It turns out that new operating system is too much for this ‘old’ model. The phone, it seems, has been pre-programmed to fail. This is what is often referred to as planned obsolescence, where products are designed not to endure but rather to be replaced on a frequent basis to feed economic demand. Most of us feel that there is something not quite right with this all too familiar scenario, and a global movement has been growing out of a desire to change it.

In 2009 a Dutch journalist called Martine Postma ran an experiment in her home town of Amsterdam. She brought together a group of handy friends and ran what she called a “Repair Café” – a free event where people could bring their broken belongings and volunteers would help to try and fix them. Following the huge popularity of the events in Amsterdam, Martine set up the Repair Café Foundation and published guidance to help other volunteers do the same in other places. A decade later, there are 1,700 repair cafes offering their services in 35 countries around the world. The grass-roots movement to bring repairing back into our economy is growing and making political demands too, taking on the world’s biggest companies through legislation that will force them to make products that are repairable and live longer.

The growth of repair cafes and the repair movement is exciting because of the potential they have to radically reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In 2017, 1.9 billion mobile phones were sold. The total carbon footprint to manufacture those phones is equivalent to Austria’s annual carbon emissions. And yet, in the EU in 2010, only 6% of phones were being reused, and only 9% were disassembled for recycling – which means that the remaining 85% of phones were left forgotten at the back of a drawer, until eventually being thrown ‘away’ to further clog up landfill sites. By simply using a phone for longer we can radically reduce carbon emissions – for example, if we used every phone sold this year for 1/3 longer, we would prevent carbon emissions equal to Singapore’s annual emissions.

The Restart Project, a regular repair cafe focused on electronic goods which started in London in 2013 has so far helped 11,942 people, aided by 18,978 hours of volunteered time working on 9,648 devices. A survey of participants attending “Restart Parties” in 2016 found that close to half of people were “slightly: or “not at all” confident undertaking repairs of their goods at home, and that 45% were unable to find a commercial repairer they could trust. Without the help of Restart volunteers, many of these goods would have been discarded. Restart calculates that their volunteers have prevented 13,817 kg of CO2 emissions from the 5,112 devices they have fixed.

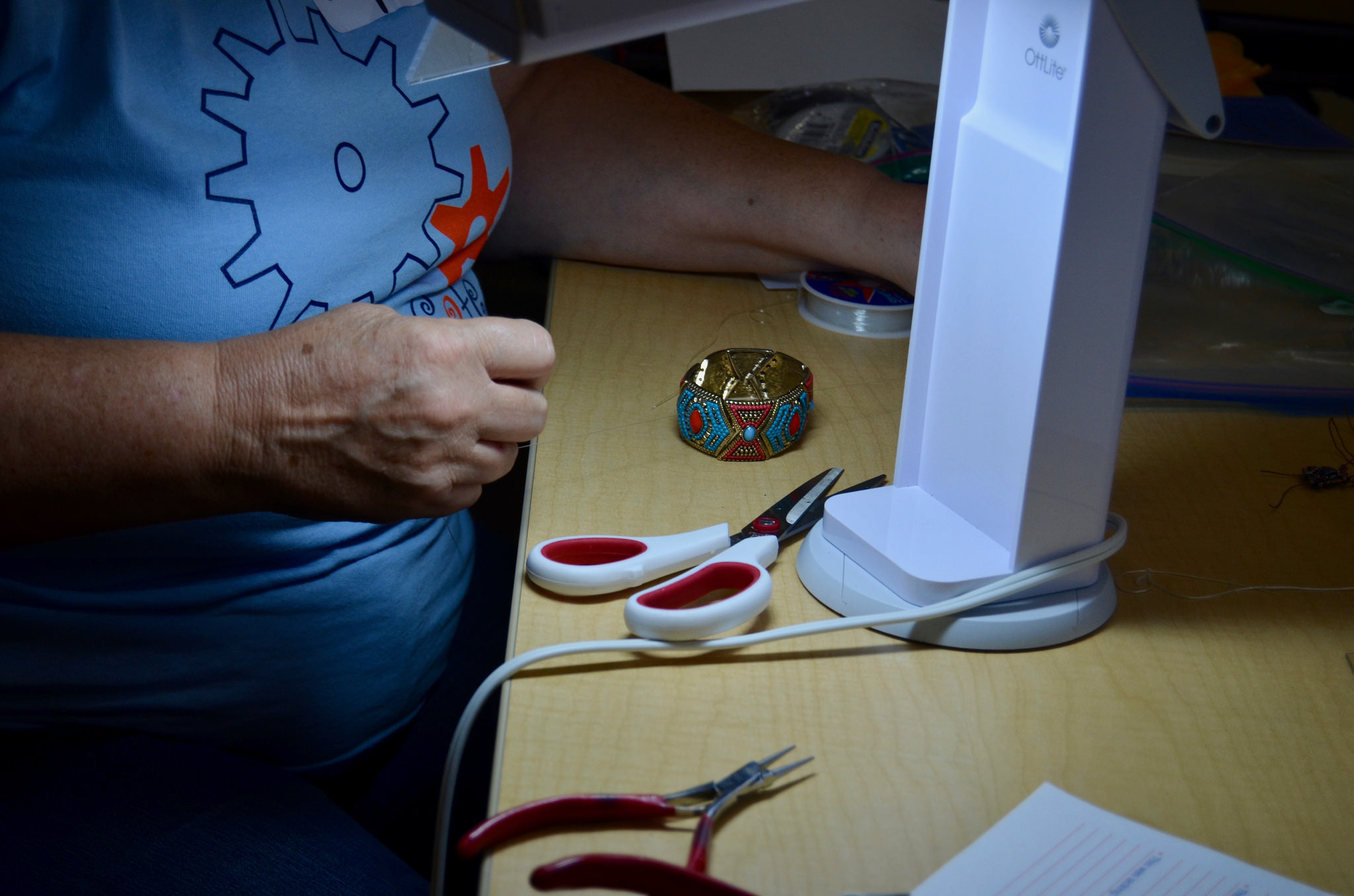

As well promoting more sustainable patterns of consumption, repair cafes seek to build communities, too. Repair cafes are socially inclusive places, with volunteers and users of all ages and backgrounds, sharing in expertise from sewing to soldering. Through the face-to-face interaction between the volunteers and people who bring in goods in need of repair, education is built into the process. Repairing is always done together with the owner watching, as the aim is to empower people to learn to feel more confident in fixing their own things.

The rise of the grass-roots repair movement is a direct challenge to the logic of our consumerist economy. Oxfam economist Kate Raworth describes the degenerative nature of industrial design within our current economic model as “the industrial caterpillar” – a linear model based on extracting natural resources, employing them in industrial processes, using the final output and, eventually, throwing it away. Raworth highlights the need to transform this linear logic of “take, make, use, lose”, into a regenerative “butterfly economy” where resources are used and re-used within the economy, and waste is radically diminished. Similar arguments were made over decades during the late 20th century by people like designer Victor Papanek and Jane Jacobs, a critic of the economic processes within cities. Both used ecological analogies to advocate better design of both products and whole economic systems. Jacobs argued for regenerative local economies that mirror ecological processes in their dynamism, rejection of waste and the way in which things can be reused and, ultimately, in how they exist in a state of dynamic equilibrium, rather than endless accumulation and growth. Repair workshops could serve as a vital building block of a future circular economy, and also help in bringing these concepts down to the tangible, community level. For the founders of The Restart Project, the local component is crucial:

“We are the inner circle of the circular economy… For us, these are the circles where we can approach a future economy on a human scale: making sure that the products we buy are more repairable, long-lasting by focusing on creating local opportunities flourish for repair, reuse and refurbishing. This is where we can transform our reality.”

The “make do and mend” culture that wartime Britain was famous for is alive and well in most developing countries today. When resources are scarce, people tend to eke as much life as possible out of the things they buy. However, in many wealthy, industrialised countries, people have more disposable income to “upgrade” their belongings more regularly, and the power of advertising has meant that repairing items that might be considered “out-of-date” has become unfashionable. A 2015 study found that between 2004 and 2012, the number of household appliances that died within five years doubled from 3.5% to 8.3%. When it comes to large household appliances, the situation is even worse, with the proportion being replaced within 5 years increasing from 7% in 2004 to 13% in 2013. An analysis of junked washing machines at a recycling centre showed that more than 10% were less than five years old.

It is not just household appliances that are being binned long before their time. An estimated 300,000 tonnes of clothing were sent to landfill in the UK in 2016, and the average estimated lifespan for a piece of clothing in the UK is a mere 3.3 years.

Consumer electronics make up the largest growing waste sector globally. In 2016, 44.7 million metric tonnes of e-waste were generated around the world – equivalent to almost 4,500 Eiffel Towers. A mere 20% of that total was collected and recycled. The booming quantities of e-waste – which is expected to reach 52.2 million metric tonnes by 2021 – can in part be explained by consumers moving on to the new and most up to date model long before their current one has failed on them. However, this wasteful model is also a function of “planned obsolescence” which is when manufacturers purposefully design their products to break down after a limited amount of time, and make them hard to fix, in order to encourage new sales. The growing backlash against the material waste from this form of consumerism – a kind of unhealthy relationship with the finite world of resources – has produced calls for a ‘new materialism’ based on the care, maintenance and repair of goods, which must begin at the design stage and be built-in.

The rapid growth of repair cafes around Europe and North America has been driven by volunteerism – groups of committed (and handy!) people who regularly give up their time to help their neighbours bring life back to their broken belongings. The social, community cohesion building element of repair cafes is fundamental to their continued expansion and popularity. Valuable practical knowledge – often held by older citizens – is being applied and passed on. With nearly 1,700 repair cafes up and running around the world, thousands of people are contributing to this grassroots movement.

Technology has also supported the development of this rapid transition. Both London’s Repair Project and the Repair Café Foundation have developed online tools which enable volunteers to collate and share data on their repairs online. Through these centralised databases, volunteers share information on the problems they faced and how they fixed them, or if they didn’t manage to. This helps build the shared knowledge and capacity of the network, and also provides hard data that repair groups are increasingly using in their advocacy.

The global repair movement is using its data and volunteers to get organised, and demand changes from manufacturers to increase the repairability of consumer goods. Repair data allows these groups to identify common problems that arise with particular products or companies, which they can take to the manufacturers to demand improvements. In October 2018, repair groups from around the UK signed the Manchester Declaration, where they ask:

“UK legislators and decision-makers at all levels, as well as product manufacturers and designers, to stand with us for our Right to Repair, by making repair more accessible and affordable, and ensuring that we adopt product standards making products better supported, well documented and easier to repair by design.”

The EU has recently responded to calls to protect the Right to Repair with proposals to extend the life and improve the reparability of lighting, televisions and large home appliances, and in the US, some 18 states are considering similar laws.