Water is life, but also the source of conflict and strife in many places. In the Indian state of Haryana, the Gurgaon Water Forum was initiated only in 2017, but has already moved quickly to build a broad network to develop a shared vision for a just transition to sustainability in the city of Gurugram, a place where many of the tensions around water management are present.

Community participation has been at the core of the vision to realize the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, like the question “Is sustainability still possible?”, the question of how to successfully involve community participation in satisfying the SDG framework is harder to answer.

Gurugram, the second largest city in the Indian state of Haryana and roughly 30 kms from the national capital, is one of the fastest growing cities in the country, both spatially and demographically. The city is dotted with swanky malls, skyscrapers and golf courses, while basic public amenities remain woefully inadequate for the poor and rich alike. Haphazard and uncontrolled growth in and around the city has had severe repercussions on local ecological systems; wetland and natural vegetation loss, and interruption of natural drainage channels are key concerns. Gurugram’s evolution as a deeply fragmented city was due partly to the way it developed – large swathes of land were acquired and developed into business/IT parks and residential colonies by private developers before trunk infrastructure could be built for the city. This, coupled with the rampant flouting of planning and construction norms, has spelt disaster in particular for the waterscape, because 70 percent of the city is reliant on groundwater sources. Groundwater levels fell rapidly from 18.7 meters (below ground level) in 2005 to 34.35 meters (below ground level) in 2014 and the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) declared the district a “dark zone” withdrawing all permission to draw on groundwater in 2016.

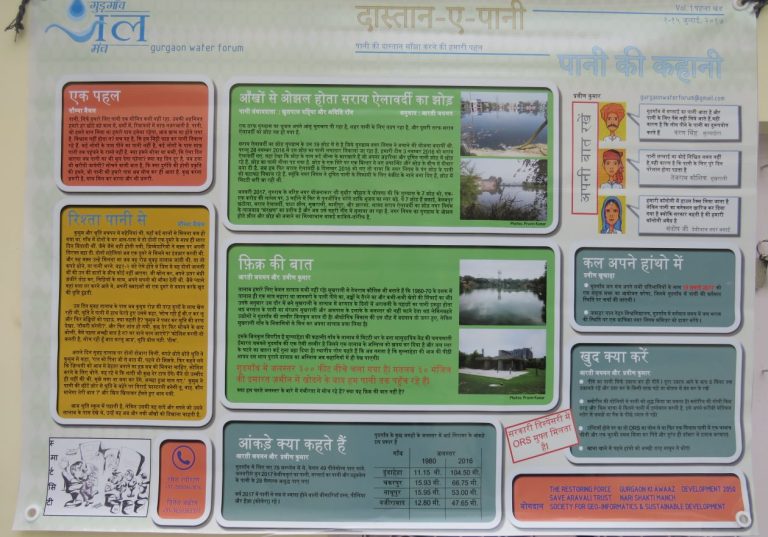

In 2017, the Gurgaon Water Forum (GWF) was initiated as a multi-stakeholder engagement forum with the intention of building a wider network of stakeholders who could develop a shared understanding of the context and a shared vision of a just transition to a sustainable city. Their aim was to keep water at the core of this transition. The GWF engaged continuously with policy makers, while also mobilizing the public. They aim to democratize access to water with the ultimate goal of making urban water systems sustainable. To achieve this, they set up a T-Lab (Transformation Lab), which is a highly-facilitated process, involving research, workshops and other forms of engagement. They’re designed to unblock complex, intractable problems (like that of growing vulnerability in the water management system) and find alternate ecologically sound and socially just solutions. This has led to water issues gaining prominence on the agenda of policymakers. The changes on the ground can be seen in formal institutions, which now appreciate that citizens ought to be part of any initiative for it to be successful and impactful.

Gurugram’s story of economic growth underscored by deep divisions and a disregard for environmental sustainability, is one that recurs across the global South. This is important because the UN estimates that by 2050, 68 percent of the world’s population will be urban and much of the addition to the urban population will be in African and Asian countries. As this inexorable urban march continues, fractious relationships between water and cities have grabbed global headlines. One such example is Cape Town’s “Day Zero” – its projection for when the city’s taps might run dry. This focused attention on several other megacities, and media outlets were quick to predict a global water crisis facing major conglomerations across the world. The interest in urban water that recent discourses in media has generated and the problems that accompany rapid unplanned urbanization (as typified by the case of Gurugram) presents us with both opportunities and challenges.

Gurugram’s inadequate access to domestic water and flooding after brief monsoon showers, Bengaluru’s lakes, and Mumbai’s increased flooding frequency show the need to understand and improve our urban water systems. Following standard global developmental paradigms has resulted in excessive attention being given to managing the supply side of urban water systems to meet drinking water targets. The disposal of wastewater and stormwater systems have meanwhile received scant attention. Dealing with the complex water issues that plague cities in developing countries requires a systems approach; urban water systems must be designed to align with hydrological regimes and geophysical realities. This is especially true in a world where climate change is a reality and “smart cities” still look towards technology alone as a panacea to fix any and all problems.

To achieve this, there is a need to unite a city that is both spatially and socially fragmented. Since most cities in the global South are more like archipelagos than networks (Bakker et. al, 2008), it is here that a multi stakeholder platform – such as GWF – can pave the way to looking for innovative solutions by providing a platform that connects people as equals. Multi stakeholder platforms, because of the diversity of experiences and knowledge that they can draw upon, provide the potential to engage on multiple fronts simultaneously, including implementation, advocacy, outreach and accountability.

Gurugram was envisioned as one of the four major satellite cities of Delhi to ease the pressure of industrial and economic growth in the national capital. The sleepy hamlet transitioned into an industrial hub in late 1970s with the establishment of one of the largest automobile manufacturing units by Maruti-Suzuki. The growth of ancillary industries like auto components, along with textile and chemical industries, transformed Gurugram into an industrial hub. After the liberalization of the Indian economy in 1990, the city developed rapidly into an information technology/business process outsourcing (IT/BPO) hub thanks to its proximity to the national capital.

Governance in the city has always been fragmented, with Haryana Urban Development Authority (HUDA), the Public Works Department (PWD) of the Haryana state government, and private developers being responsible for service provisioning in different parts of the city depending on their respective jurisdictions. Gurugram was a relatively small urban area and did not acquire the status of a city till 2001. It was governed by a municipal council and was directly controlled by the Chief Minister’s Office, making it easy to get requisite clearances for changes in land use plans. The city landed its first Municipal Corporation in 2008. In 2017, the Gurugram Metropolitan Development Authority was created by an Act of the State Legislature “to develop a vision for continued, sustained and balanced growth of the Gurugram Metropolitan Development Area through quality of life and reasonable standard of living” (GMDA Act, 2017).

The city’s population grew from 0.87 million in 2001 to 1.51 million in 2011. A huge influx of migrants (both white-collared and blue-collared) created a boom in speculative real estate development plus large unauthorized colonies inside these “urban villages” catering to various segments of the migrant community. The lax implementation of land use plans and a booming construction industry (which relies heavily on illegal boring of groundwater) led to rampant encroachment onto common property and resources. This resulted in the shrinking of wetlands, disruption of natural drainage channels and a drastic reduction in groundwater levels. Meanwhile inadequate public water services forced people to either rely on tankers or borewells for their domestic water needs.

The shift from apathy to one of active involvement of the public administration in managing urban water in an integrated framework has been possible because of sustained pressure by citizens groups and forums such as GWF.

The approach of GWF helped distinguish itself from the middle-class activism that has increasingly drawn criticism for its exclusionary civil and political representation in Southern cities. It has stayed true to its nature of a multi-stakeholder platform and its aim of amplifying the voices of the working class. Bringing together different groups such as key government representatives, resident welfare associations (RWA), trade unions, environmental activists, higher educational institutes, women’s welfare groups, and urban planners has ensured that the siloed approach to urban water is questioned and a useful conversation is initiated. The inclusion of different groups helped to forge a shared understanding of the contexts of urban water problems and the possible pathways towards a just and resilient waterscape.

One of the primary reasons why multi-stakeholder platforms collapse is excessive focus on dialogue without involving people in real action. GWF has consistently focused on engaging stakeholders not just in dialogue but in co-producing knowledge and real solutions to problems, such as designing dual water supply systems for neighbourhoods. The idea of co-producing and co-designing solutions also helps ordinary citizens better understand issues of scale – what kind of actions can be taken at an individual level, at the level of the community (such as RWAs) and which actions would need the larger involvement of the district administration (such as rainwater harvesting in open spaces), and how these disparate initiatives might form a coherent sustainable urban water system. GWF’s facilitation of knowledge sharing between domain experts, administrative officials, and ordinary citizens has helped provide alternative solutions and practices for all stakeholders.

During the extensive research period before conducting T-Labs and GWF’s subsequent engagement and interaction with different stakeholders, a lack of data made it hard to generate proposals for policy makers. By analysing the spatial growth of the city using GIS and mapping its impact on natural water bodies, it became possible to communicate to policymakers the urgency of taking immediate steps to revive natural water bodies and protecting the catchment areas from further degradation.

In terms of advocacy and outreach, structured facilitated processes such as T-Labs have been supplemented by more informal approaches to ensure a wider and continuous engagement with stakeholders. Weekly radio programs in local community radio stations and informal mohalla-sabhas (neighbourhood meetings) have been instrumental in providing inputs to GWF and the administration about actual on-ground conditions. Similarly, organizing science clubs in local public schools have helped in reaching out to young adults and moulding them into water-conscious citizens, while also expanding the forum’s outreach activities.

Assistant Professor at Centre for the Study of Regional Development (CSRD) at Jawaharlal Nehru University, which hosts the Steps South Asia Sustainability Hub, a member of the Rapid Transition Alliance.